A Tale of Two Bugeyes

By Patrick Boyle and Brendan Burke

The mid-Atlantic oyster industry is one of the oldest fisheries in the United States. Today, it continues today to define the character of the Chesapeake Bay. For millennia, Virginia Indians harvested oysters from shoreline beds as well as deeper waters (Jenkins and Gallivan 2020). During the 17th century, European colonists turned to oysters not only for food but as a key component in lime mortar for masonry structures. Burned oyster shells, slaked with water, literally helped form the foundation for some of Virginia’s earliest historic architecture. As coastal communities developed during the 19th century, oystering became a profitable enterprise throughout the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. The development of railroads significantly impacted the oyster industry as did preservation by canning. Shipment of northern ice to the south, and ultimately the ability to manufacture ice at the local level, further stimulated oyster fishing. Fresh and canned oysters were loaded onto trains bound for inland cities with eager consumers. Expansion led to innovation in fishing techniques and vessel types that formed around an emergent commercial industry (Chestnut 1951:142).

Development of commercial oystering was slow to appear during the 17th and 18th centuries yet consumption of oysters was widespread in the Tidewater. Oysters were largely eaten by people living along waterways who had access to oyster grounds. Fishermen supplied fishmongers for urban needs but were more often generalists selling what the net caught. As the oyster industry grew, oyster grounds along and near the shore dwindled. For oystermen, that meant heading to more distant fishing grounds and larger boats with specialized tools such as iron-tipped oyster tongs or a dredge. An oyster dredge was an iron toothed heavy rake with a trailing chain basket. Teeth on the leading edge of the dredge uproot oysters from a ‘rock’, which then fall into the basket for retrieval.

The dredge is let out on a towing wire and recovered by a mechanical winch called a ‘winder’. By the mid-19th century, dredging was a common method of harvest throughout the Chesapeake Bay. At the same time, additional pressure was placed on the resource as New England’s oyster grounds were depleted and boats moved south (Brewington 1963:62; Brugger 1996:787; Wennersten 2007:5). Dredging was banned in some areas since the harvest was so efficient and culled shell was infrquently redeposited to the habitat.The Civil War temporarily halted oystering in the mid-Atlantic as fishermen entered service and non-military boats operating in Tidewater were often suspected of aiding one side or the other. Prices rose as demand increased and supplies diminished. At stations and outposts along the coast, soldiers were introduced to oysters and that appetite went home with them when peace returned in 1865. A post-war gold rush for oysters began and fishermen convinced legislatures to lift anti-dredging laws to boost the catch. It was time for a new vessel, one purpose built for dredging the Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay Bugeye

Sailing vessels of many shapes and sizes tramped up and down the Chesapeake Bay during the mid-1800s. Vernacular (meaning regionally-specific and built on custom and not designed by a professional naval architect) vessels of the Bay included the brogan, pungy, Poquoson sailing canoe, pinky schooner, scow, and log canoe. The Civil War brought alien watercraft to the area as the army and navy needed patrol boats, gunboats, tugs, and transports. Fishermen from New Haven and other Yankee ports sailed their shallow draft ‘skimming dishes’ south as well to find fresh oyster grounds but it was native Chesapeake boat builders who designed a wholly new vessel to ‘drudge arsters’.

Larger sailing vessels of the Bay were simply too deeply drafted to serve in the oyster dredging business. A revolutionary new concept, the centerboard, was adapted to the uniquely-Chesapeake log-bottomed boat. The result was a shallow-draft two-masted vessel purpose built for the oyster fishery. And - before you ask - no-one knows exactly where the name came from, but it stuck.

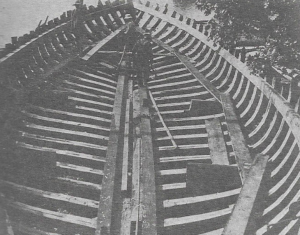

The first bugeyes were constructed about 1867 and were a hybrid vessel adapting the log canoe bottom to a schooner-style upper hull. Early bugeyes were constructed from heavy logs joined together with iron pins. The shape of the hull was chopped out with adzes. Log-bottomed bugeyes had a central keel log with as many as five logs on either side. The outermost logs, called ‘wing logs’, contained the ‘turn of the bilge’ where the relatively flat bottom of the boat turns upward. Frames overlapped the log bottom and milled planks carried the hull upward to the cap rail. A heavy centerboard, which resided in a watertight case in the middle of the hull, could be lowered below the keel log, through a slot, to help bugeyes sail straight instead of being pushed sideways through the water. Typical construction methods of bugeyes varied from builder to builder, many of these subtle differences went undocumented but were unique to the shipwright. Building a log-bottomed bugeye took at least five large pine trees from which a timber eighteen inches square by forty feet long could be cut. The wood had to be free of knots and tight-grained. Pines of that magnitude became increasingly harder to source and by 1880, the first plank-on-frame bugeyes were built which did not need the large ‘chunk’ timbers (Brewington 1963:44; Chapelle 1982:257). Those boats retained the same shallow draft, flat bottom of the log boats but were built using more typical ribs (frames) overlaid with outer hull plankin..

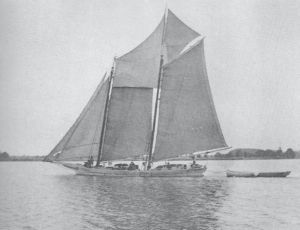

Variations in design emerged from yard to yard as builders made improvements or adapted the vessels for specific traits. Above the deck, bugeyes traditionally carried two masts and the foremast was taller than the main mast. Normally considered a ‘ketch’ rig, it was locally known as the bugeye rig. Vessels outfitted with this mast arrangement hoisted ‘leg-of mutton’ sails, a simple triangular sail. Only a very few of the more than 600 bugeyes built carried a schooner rig and were often known as ‘square-headed’ bugeyes.

Bugeyes, or ‘Buck-eyes’, proliferated throughout the Chesapeake Bay through the last quarter of the 19th century and by 1900, served outside the Bay as far as New Jersey to North Carolina. When not dredging oysters or hauling her catch, the boats were put into the freight business hauling potatoes, watermelons, lumber, fertilizer, coal, or mixed cargoes.

The Hobbs Wreck

In 2019, a team of archaeologists from the St. Augustine Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP) and Longwood University recorded thirteen vessels in the Nansemond River near downtown Suffolk. One of the vessels was a bugeye, which soon became known as the Hobbs Wreck after Kermit Hobbs, a local citizen and historian who reported the wreck. Research into this abandoned bugeye revealed a chapter of Suffolk forgotten by many and unknown to most. Aboard this vessel, and on an adjacent wharf site, the modern oyster industry was born.

The Oyster Industry of Suffolk, Virginia

The gold rush days of oystering centered around the 1880s when the largest catches of oysters were ever recorded. Nearly fifteen million bushels of the bivalves were dredged or tonged up. There was good money to be made oystering, which attracted the attention of men with capital to invest in boats, fish houses, and distribution networks.

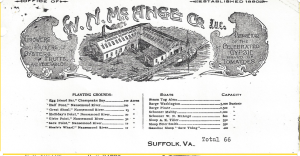

William Norman McAnge, a magnate of the turpentine industry of South Carolina, moved to Suffolk in 1880 with hopes of gaining a foothold in the prosperous lumber industry. Shortly after settling in the area, McAnge established an oyster house on the south bank of the Nansemond River (Evans 1899:1011-1012). Before shipping, oysters were typically shucked, cleaned, iced and packed in tin cans at the oyster house. The oysters were then shipped via railroad to inland markets. Though McAnge canned oysters in Suffolk, he also shipped live oysters in iced barrels. It was this move ‘from bucket to barrel’ that dramatically increased the city’s export of ‘shuckers’ and leveraged the new availability of ice to expand the fresh seafood market. McAnge, like many of his colleagues, saw decreasing catch rates each year and recognized the threat of overexploitation. To guard against collapse of the fishery, McAnge pioneered oyster leases in the James River and near the mouth of the Poquoson. Unlike many fishermen who fought over public grounds, McAnge took his future into his own hands by leasing bottomlands and growing oysters. His fishing empire expanded and by the early 1900s McAnge’s vessels sailed up to New Jersey and down to North Carolina to source and sell the delicious, fresh oyster.

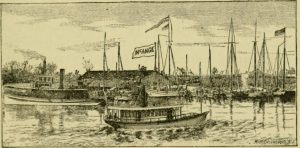

McAnge owned a fleet of oyster boats (Figure 6) and was the likely owner of the Hobbs Wreck. That vessel was one of the few schooner-rigged bugeyes and likely serviced McAnge’s oyster leases as a dredge boat. Remnants of scallop shells in the mud around the Hobbs Wreck also prove out McAnge’s connection to ocean fisheries since the large scallops are only found in deeper Atlantic waters.

A Backwater Bugeye (PMR0062)

Submerged in the shallows of the Pamlico River, across from the historic port of Washington, North Carolina, are the bones of an abandoned wooden vessel. At low tide a centerboard case can be seen protruding through the black water. During occasional “blowouts”, when strong westerly winds push water out to the Pamlico Sound, wooden frames and planks of the wreck are exposed. Though known by locals, the story of the boat is lost to local lore.

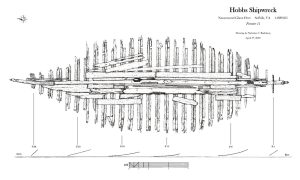

In 2020, a research team from East Carolina University’s Program in Maritime Studies surveyed the vessel as part of their fall field school. The wreck measures 15.6 m (51 ft.) long, 5.2 m (17ft.) wide, and is plank-on-frame constructed. After decades of slow decay, only the bottom of the hull remains. Structural features of the hull include the stem and stern assemblies, a centerboard case, and twenty frames. Thirty-six artifacts were also found and recorded on the site, which include oystering tools and rigging equipment. The wreck was initially hypothesized as a locally built centerboard schooner, but diagnostic elements of the hull, including offset placement of the mainmast step, indicate the vessel was a Chesapeake Bay bugeye with the same schooner rig as the Hobbs Site.

North Carolina Oysters Invade the Chesapeake

The gold rush days of the Chesapeake Bay oyster industry began to wane during the 1890s and the industry pushed further south to find untapped fishing grounds. The Currituck, Pamlico, and Albemarle sounds of eastern North Carolina were soon crawling with Chesapeake boats.

The Inner Banks were largely rural and sparsely populated during the late 19th century. Unlike the Chesapeake, there were few rail heads, ice houses, and urban centers to host a fleet of oyster boats. New Bern and Washington were the largest communities on the sounds and attracted investment from Maryland and Virginia oystermen. William McAnge was among them and his boats regularly sailed from Suffolk into Tarheel waters. In 1890, the J. S. Farren Canning Company established an oyster cannery in Washington. The Baltimore-based company hired over 150 employees and literally paved their way into the community by providing oyster shell for the town’s streets (Washington Progress 1896:3; Harding 1976:506).

During the first decade of the 20th century, Farren packed and shipped hundreds of thousands of cans to their Baltimore headquarters for distribution. In a marketing sleight of hand, North Carolina oysters were sold as Chesapeake Bay oysters to capitalize on the name recognition. Predictably, oysters in Old North State were gobbled up by the early 20th century and the fishery collapsed. Bugeyes and skipjacks sporting Virginia and Maryland homeports dredged the sounds empty. Less than two decades after the Farren cannery opened its doors, it began to throttle back production and lay off workers (Washington Daily News 1909:1).

Archaeological Significance

Something ‘significant’ is worthy of attention and as archaeologists we are often challenged to reveal significance from the tattered remains of human enterprise. Broken pottery, remnant bones of ancient meals, lost buttons, you know the drill. Taken individually, artifacts may appear bland or valueless, but use them to reconstruct a past and we can glimpse generations long gone. Shipwreck sites, whether abandoned vessels such as these, or ships lost in transit, such as the Titanic, are complex archaeological sites. The structure of the vessel contains thousands of components, each a product of technological innovation or human artistry. Material culture, from cannon to cargoes, carried within a vessel speak to communities beyond the waves. These two oyster boats were technological innovations of their time. The design was a response to environmental change wrought by economic shifts. Their crews and owners redefined the character of the Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina’s sound country. That both vessels were schooner-rigged bugyes reveals rare comparative samples of a unique chapter in commercial fisheries.

The maritime history of the Chesapeake Bay is simply breathtaking. From Pleistocene mammoth hunts 15,000 years ago to the menhaden fleets of today, the world’s largest estuary may also be the world’s most diverse estuary. As you read this, ships churn their way in and out of the Bay with global cargoes. Beneath its waves are hundreds of silent wood and steel wrecks, each with their own miniature contribution to history. Sailors and fishermen here have taken every hue of skin, age, and identity. Every single one of them had a story. Their working worlds, hewn from trees or beaten from iron, hold those stories and it is the job of archaeologists, sometimes working underwater, to reveal them. For some crew, fishing meant freedom from land and entanglements ashore. For others, it may have been a wooden prison, freezing in winter and sweltering in summer. The oyster fleet was a floating community where distant boats could be identified by the ‘cut of their jib’ or a subtlety lost to you or me. Bugeyes formed a wooden backbone for maritime commerce and were the largest single investment of many families. Their wooden bones, hidden in marsh mud or beach sand, hold forgotten stories worth finding and hearing.

References:

Brewington, M. V.

1963 Chesapeake Bay Log Canoes and Bugeyes. Cornell Maritime Press and Tidewater

Publishing, Centreville, MD.

Brugger, Robert J.

1996 Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980. Johns Hopkins University Press,

Baltimore, MD.

Chapelle, Howard

1982 The History of American Sailing Ships. Bonanza Books, New York.

Chestnut, Alphonse F.

1951 The Oyster and Other Mollusks in North Carolina. In Survey of Marine Fisheries of

North Carolina, pp. 141–190. Chapel Hill, NC.

Evans, Amanda M., editor

2016 The Archaeology of Vernacular Watercraft. Springer, New York, NY.

Harding, Pauline Marion

1976 Ships That Pass in the Night. In Washington and the Pamlico.

Jenkins

Washington Daily News

1909 Many Oyster Boats. Washington Daily News. 13 November:1. Washington, NC.

Washington Progress

1896 Our City to Have Shelled Streets. Washington Progress. 31 March:1. Washington, NC.

Jenkins, J. and Martin Gallivan

2020 Shell on Earth: Oyster Harvesting, Consumption, and Deposition Practices in the Powhatan Chesapeake. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. Vol. 15. Pp. 384-406.

Publishing, Centreville, MD.

Wennersten, John

2007 The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay. Eastern Branch Press, Washington, D.C.