Cornerstone Contributions: Reconciliation and Reconstruction in Two Hand-Carved Wooden Keepsakes

Warning: Images and content may be offensive to some viewers. Proceed at your own risk.

Two carved wooden memorial objects (Figures 1, 2), created by the same hand, were carefully enclosed in an envelope and placed within the copper box ceremonially laid beneath the Lee monument cornerstone. Both items were intended to be viewed in three dimensions: the front, sides, and back are highly detailed. One relic represents the Confederate Battle Flag and the other relic represents the square and compasses: the emblem of the fraternity of Freemasonry. Not only were these objects symbols of their time, but the very material from which they were carved had deep, reverential meaning. Lea Lane, of Preservation Virginia, contributes fascinating research into the material and the likely identity of the artist, while Laura Galke of the Department of Historic Resources considers the social context and evolving meaning of these symbols over time.

The outside of the envelope, which contained these two wooden objects, included a handwritten note:

“Battle flag + square + compass made from the tree that was taken from Jacksons Grave in Lexington, Va. by Capt. J. W. Talley”

Humans have long recognized that the roots and branches of trees serve as silent observers of the history that plays out under their canopy.[i] They are revered as enduring witnesses. However, some Civil War witness trees were turned into relics even before the smoke of battles dissipated. Woody plants, especially when shredded by artillery fire, were easy fodder for the busy knives of soldiers on both sides of the conflict, who transformed them into smoking pipes, rings, and other small carvings. Indeed, the enthusiasm with which the soldiers carved was described at the time with obsessive language: mania, disease, rage, fever.[ii]

The objects they made were inextricably linked to the events and landscapes of their experience—even if the carving themselves had no visible reference to that origin. Such is the case with the Masonic compasses and square (Figure 1) and the Confederate flag (Figure 2) donated to the cornerstone box by Captain J.W. Talley. Without the information included in the newspaper coverage of the dedication, they are potent symbols. With the knowledge of their connection to General Jackson’s burial site, they assume a more complex identity, bound tightly with their material origin.

The tree that grew beside Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson’s grave in Lexington was a Paulonia imperialis, commonly known as a Princess or Empress tree (Figure 3). They are native to China, and burst forth with lavish foxglove-like flowers in the spring. They grow rather quickly—a recent study found a 20-year-old Princess tree in Kentucky that had already reached a diameter of 20 inches, and a height of 62 feet.[iii] Although only planted in 1864, by 1884 it had noticeably disturbed the burial site. The root system of this tree aggressively spreads during the early years of growth. Reports from the 1884 removal note how the “roots had gone directly to the coffin and embraced, by curious curves and bendings, the body.”[iv] It had reclaimed the very material of Gen. Jackson in its growth—less of a witness tree, and more of a participant.

The sexton of the cemetery, W.C. Charlton, oversaw the removal of the tree (and the move of the graves themselves later in the century). He gave a cane and a portion of the material to Reverend John J. Lafferty. From this wood, Rev. Lafferty made or commissioned several objects, which were sent to “men who honor the memory” of Jackson—at least two gavels, and one turned acorn (Figure 4) which is now in the collection of the American Civil War Museum.[v]

It is certainly possible that Rev. Lafferty also commissioned the carvings that were included in the cornerstone box. The report on the box only notes the source of the wood and the donor’s name, J.W. Talley, not how he obtained the material or finished items. Perhaps Capt. Talley was among those identified by Rev. Lafferty as “men who honor the memory” of Jackson.

There are a couple of potential candidates for “Capt. J.W. Talley.” One strong option is Capt. John Winn “Jack” Talley (1844–1902), who served with the 3rd Virginia Cavalry. After the war, he became a well-known river captain and railroad conductor who had a later career as a hotel proprietor in Lexington and Buena Vista, Va. He was in the Lexington area in the years immediately after the removal of the tree from Jackson’s gravesite, and thus may have been able to obtain a portion of the material. He is known to have visited Richmond at the end of September 1887, less than one month prior to the cornerstone box dedication.[vi]

In 1897, he was the commander of the Blue Ridge camp, United Confederate Veterans.[vii] His post-war veteran activity may have also included riding with General Fitzhugh Lee at the dedication of the Soldier and Sailors monument in 1894.[viii] John W. Talley was a highly ranked Freemason, an appropriate background for the donor of a symbol of the group. In fact, his gravestone in Buena Vista is prominently carved with the compasses and square.

Why were these particular symbols important to those preparing for the statue’s dedication in 1890? In the decade preceding the American Civil War, Freemasonry grew popular and become one of a number of secret, fraternal societies. Men boasted their membership during peacetime by wearing the square and compasses on their lapels and watch chains. These tools, the square and compasses, represent stonemason’s tools and reminded members to behave in accordance with the high standards of Freemasons.

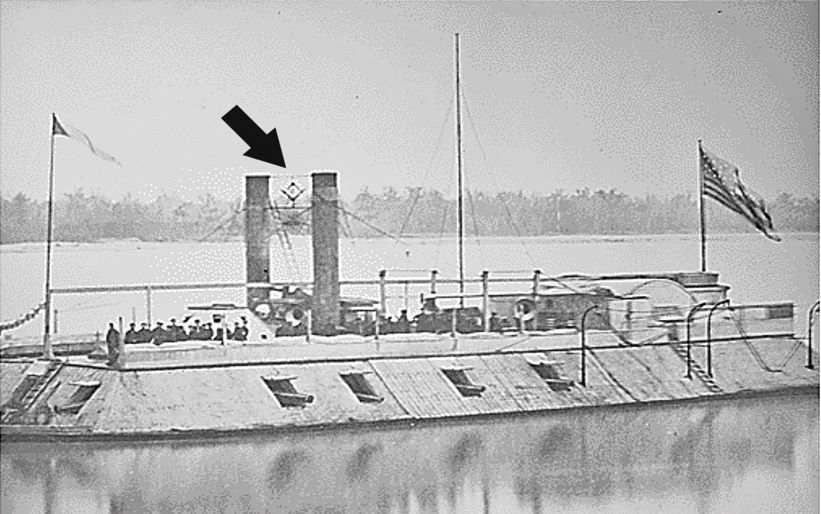

During the Civil War, wearing Masonic pins—popular among soldiers of both armies—signaled membership in this secret fraternity. When worn as part of a uniform or embellishing rustic quarters or ironclad ships, these symbols entitled the owners to the privileges of this fraternal brotherhood. A system of signs, gestures, and signals notified others of their membership, overtly or covertly, as the situation warranted. This was no trifling club: displaying this symbol was an informal request by members for accommodation from fellow members—including enemy combatants—who had taken a solemn Masonic oath to provide comfort to any fellows in distress and to provide for their surviving families.

It seems members of the Union ironclad USS Baron De Kalb proclaimed their membership, displaying what appears to be the square and compasses (Figure 5). Numerous examples of soldiers helping one another have survived.[ix]

The Confederate Battle Flag, commissioned by General Pierre Beauregard and designed by William Porcher Miles, was an interesting subject for Captain Talley to carve and memorialize in the cornerstone box. The rectangular flag used an X-shaped pattern known as the St. Andrew’s Cross, and was emblazoned with one star for each seceding state. Although it was popular, the flag was never adopted as the Confederacy’s official symbol. The carving differs from the Confederate Battle Flag in that it exhibits eleven stars, not thirteen as seen in the flag design. This was possibly the result of the size of the carving.

At the time these items were enshrined within the Lee Statue in 1890, the ‘New South’ embraced a revisionist history of the Civil War, one in which slavery as a root cause of the war was rejected. Some scholars refer to this period, from the 1890s-1920s, as the “Vindication of the Confederacy” phase of reimagining the Civil War.[x] The modest obelisks that quietly adorned cemeteries in the decade after the Civil War had evolved to large statues portraying prominent Confederate military leaders in public spaces, such as courthouse grounds and state capital lawns. These public monuments bolstered a revisionist history of the Civil War that imagined benevolent slavery and the supremacy of Confederate military leadership and promoted a racial hierarchy.

In 1890, Capt. Talley clearly embraced this revisionist history. As a piece of material culture, the flag's meaning has changed over time. Its messages are intentional and powerful. In 2022, this represents a captured flag, now invalid. As communities consider the future of existing statues and the creation of new memorials, they do so with the knowledge that monuments are not passive objects, but ones that actively inspire, discipline, and guide all who encounter them for generations.

—Laura Galke, DHR Chief Curator, and Lea Lane, Curator of Collection for Preservation Virginia

•••

References

[i] Witness Trees, American Battlefield Trust, April 16, 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/head-tilting-history/witness-trees; Mike Yessis, These Five “Witness Trees” Were Present At Key Moments In America’s History, Smithsonian Magazine, August 25, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/these-five-witness-trees-were-present-at-key-moments-in-americas-history-180963925/

[ii] Cambridge Chronicle, May 3, 1862; History of the Fifth Massachusetts Battery, United States, L. E. Cowles, 1902; James Madison Drake, The History of the Ninth New Jersey Veteran Volunteers, United States, Journal Printing House, 1889; History of the 1st Illinois Light Artillery, Cushing Printing Company, Chicago, 1899.

[iii] Christopher R. Webster, Michael A. Jenkins, Shibu Jose, “Woody Invaders and the Challenges They Pose to Forest Ecosystems in the Eastern United States,” Journal of Forestry, 2006, 104 (7): 366-374.

[iv] Monroe, Louisiana Daily Telegraph, June 2, 1886

[v] Vicksburg, Mississippi Weekly Commercial Herald, April 23, 1886; Indianapolis Indiana State Sentinel, 16 Jun 1886; The Norfolk Landmark, December 4, 1890

[vi] Richmond Dispatch, September 30, 1887

[vii] Confederate Military History, Volume 3, 1899, pg. 1197

[viii] “Unveiling of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument,” Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. XXII, 1894, pg. 343.

[ix] Halleran, Michael A. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Freemasonry in the American Civil War. University of Alabama Press, pg. 160-166

[x] Brown, Thomas J. 2019. Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

•••

Further Reading

Bare, Steven A. 2019. “The Sinews of Memory:” The Forging of Civil War Memory and Reconciliation, 1865-1940.

Brown, Thomas J. 2019. Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Carpenter, Lucas. 2001. "Old Times There are Best Forgotten: The Future of Confederate Symbolism in the South." Callaloo 24(1):32-37.

Cox, Karen L. 2020. “Markers, Monument, and Meaning – A National Conversation.” Webinar hosted by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Available https://www.wisconsinhistory.ort/Records/Article/CS16419.

Cox, Karen L. 2003. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Curry, David. 2003. “The Virtuous Soldier.” In Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory, edited by Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, pp149-162.

Davenport, Guy. 2001. "The Confederate Battle Flag." Callaloo 24(1):51-54.

DeGuzman, Maria. 2001. "X-ing the Flag." Callaloo 24(1):55-59.

Evans, Jocelyn J. and William B. Lees. "2021 Context of a Contested Landscape." Social Science Quarterly. 102(3):979-1001.

Halleran, Michael A. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Freemasonry in the American Civil War. University of Alabama Press.

Hayden, Jessica M. 2021. "Confederate Imagery in Congressional Rhetoric: Divisions and Deliberation." Social Science Quarterly 102(3):1084-1097.

Marsden, Scott. 1996. "The Damned Confederate Flag: The Development of an American Symbol, 1865-1995." M.A. Thesis, Department of History and Classics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Martinez, J. Michael, William D. Richardson, and Ron McNinch-Su (editors). 2000. Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Mullins, Paul R. 2021. Revolting Things: An Archaeology of Shameful Histories and Repulsive Realities. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Rutyna, Richard A. and Peter C. Stewart. 1998. The History of Freemasonry in Virginia. University Press of America, Inc., Lanham.

Silber, Nina. 2016. "Reunion and Reconciliation, Reviewed and Reconsidered." The Journal of American History 103(1):59-83.

Strother, Logan. 2021. "Racism and Pride in Attitudes toward Confederate Symbols." Sociology Compass. 15(6):1-12.