Cornerstone Contributions: Analyzing the Past: Analysis of Carlton McCarthy’s Army of Northern Virginia Badge

The author describes the challenges inherent in the preservation of artifacts composed of different materials, and in the specific identification of each of those materials. The particular example discussed in this post is an Army of Northern Virginia Badge included in the Lee Monument cornerstone by Carlton McCarthy, mayor of Richmond from 1904-1908.

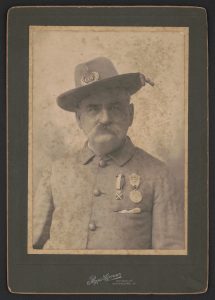

Nestled among the belongings of Richmond Mayor Carlton McCarthy, the cornerstone box revealed a small medal suspended on a ribbon. This object is one of only three textile-based artifacts found within the box. On first glance, the medal appears to be an enamel Confederate flag attached to a red and white striped ribbon that is missing the pin. The placard is the Army of Northern Virginia Battle Flag inscribed with “A.N.V” at the bottom [1]. Other iterations of this medal are marked with the respective soldier’s division or engraved on the back, but McCarthy’s award is not personalized.

Composite artifacts present a conundrum to conservators. Different materials require different preservation methods; a composite object requires conservators to prioritize one treatment over another. In the case of the medal, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR) lab decided the object should not be placed in silica gel like the rest of the metal objects. Silica adsorbs water to prevent metal corrosion. However, this loss of moisture can also render textiles brittle and more fragile. Given the medal is one of few textile artifacts found within the cornerstone box, the DHR lab prioritized the safety of the ribbon and did not place the object with silica.

Identifying the ribbon’s fiber proves challenging, even though the artifact predates synthetic textiles. The ribbon could be woven from cotton, flax, or silk. Given the object is a military award, a silk ribbon would be a likely choice. However, the ribbon exhibited a ridged cord weave that would be an unusual pattern for silk. Satin weaves are more commonly used to highlight the fiber’s luster while cord weave is ridged for strength. Examination of the ribbon’s fraying edge also yields no answers. The threads possess a sheen, which may indicate silk, but this property does not eliminate any possible materials for this textile.

Under a microscope, flax appears visually similar to bamboo with segmented units defined by rings. Cotton looks like flattened and twisted tubes. Comparatively, silk appears flexible and smooth. These microscopic structures affect the properties. The mercerization process used on cotton and flax was invented in 1844. This is a process that improves the luster, strength, and dye uptake of both cotton and flax by regularizing their microscopic structures [2]. While silk can usually be recognized for its shiny smoothness, once cotton and flax are mercerized they are difficult to discern from silk by eye.

The ribbon is discolored: the red has faded and the white has yellowed. Additionally, there are tide lines at the border between the colors, indicating the red dye is not sufficiently colorfast. Potential natural dyes include cochineal and madder, which can be successfully applied to both protein and celluloid based fibers.

However, the manufacture of the ribbon may have been concurrent with the invention of synthetic dyes. The dates on the medal note the full duration of the Confederacy from 1861-1865, meaning the medal could have been issued anytime from 1865-1887. Notable figures like Julia Christian (née Jackson), daughter of General “Stonewall” Jackson, were issued honorary A.N.V medals after the conclusion of the war. Given that the medals were not distributed in connection to a particular event or date, their date range could include the birth of synthetic dyes.

A possible synthetic red dye is alizarin red, which was synthesized from madder in 1869. It's invention toppled the cultivation of natural madder dye throughout Europe [3]. In 1881 the French district of Midi produced over half of the world’s madder. By 1886, the township sold no dyestuffs due to competition with alizarin red [3]. The red dyed ribbon could be anything from natural madder, natural cochineal, or synthetic alizarin.

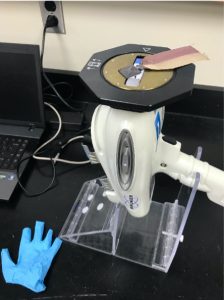

Unlike the ribbon, the composition of the metal placard of the award is far more forthcoming. The DHR conservation lab uses a portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF) machine for identifying non-organic elements, such as the metal used to make the placard, and the composition of the enamel pigments. The machine uses X-rays to excite the electrons of the object being scanned. As the electrons give off their extra energy, they revert to their usual state. The machine is able to identify the unique distances between energy levels, which correlate to specific elements as the electrons move from their excited energy state to their normal energy state.

Scanning the placard revealed that the medal is brass, as the pXRF indicated the presence of both copper and zinc. The red and blue enamel within the Army of Northern Virginia Battle flag were determined to be a lead-based pigment and a copper-based pigment, respectively. Copper’s corrosion products can be red, blue, or green in hue. Artists and pigment manufacturer’s took advantage of this to make blue pigments. These metals could be informative regarding the availability of materials, if examined alongside other artifacts produced before, during, and after the Civil War.

Many of these questions could be definitively answered with further analysis. But some of these analytical techniques could be destructive. Even snipping a piece of unraveling thread from the ribbon compromises the integrity of the original artifact. The DHR is not the permanent owner of the cornerstone box and its artifacts, so any destructive testing will not be conducted at this time. Questions regarding post-War industry and materials are best answered through other, more common artifacts. This medal is unique, given its association with the cornerstone box and Mayor Carlton McCarthy.

—Hannah Sanner

Conservation Intern, Department of Historic Resources

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR's archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

Footnotes:

[1] John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem, 2005, 3-4.

[2] J.T Marsh, An Introduction to Textile Finishing, 1948, 111-133.

[3] Francois Delamare and Bernard Guineau, Colors: The Story of Dyes and Pigments, 2000, 101-102.