Learning Through Artifacts: My Internship Experience with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources

During the writer’s summer internship with DHR, she catalogued colonial artifacts from a 17th-century Virginia site known as The Maine. Through this experience she gained a deeper understanding of how everyday objects, specifically clay tobacco pipes, can reveal detailed information about early colonial life in Virginia.

By Caroline Beigel | Intern, DHR Division of State Archaeology

During my internship with DHR, I had the opportunity to dive into the collection of a site that not only increased my knowledge of colonial artifacts but also changed my perspective on archaeology. Over the course of ten weeks, I worked alongside collection managers, curators, conservators, archaeologists, and volunteers. I attended lectures based on my interests, as well as ones pertaining to the work that I was doing. One of my favorite lectures was on historic ceramics; I found examples of what I learned within the collection I was cataloging for the internship. The professionals I worked with were a great resource when I had questions, and I learned that with artifacts, there are always questions.

It was my responsibility to catalogue and re-house artifacts from a Virginia site called The Maine, which was excavated in 1976 by archaeologists Bill Kelso, Alain Outlaw and their team. The site got its name from its location on the mainland northwest of Jamestown Island, though it was known as Tsenacommacah to the Native Americans who occupied the area. The initial expansion of land acquisition and development outside of Jamestown onto the mainland was prompted by the successful cultivation of tobacco, and large plantations were needed to keep up with the demand for tobacco in England. The Maine was occupied during the first quarter of the 17th century by investors and tenants of the Virginia Company. Life was difficult for these early colonists as they faced many challenges, from food shortages to conflicts with the Native Americans whose lands they now occupied, to difficult environments and a constantly declining population. Due to these obstacles, The Maine became one of only a few plantations the English decided to hold and defend (Outlaw 2025). The artifacts recovered from The Maine give insight into what day-to-day life could have looked like for these people of whom there are so few written records. I started this internship after reading the site’s excavation report, and I understood that the artifacts would be fundamental in telling the story of the site and its inhabitants.

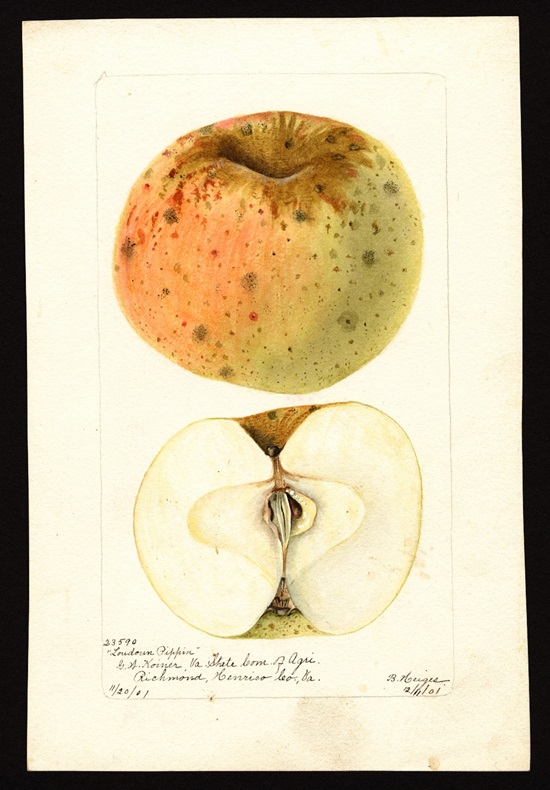

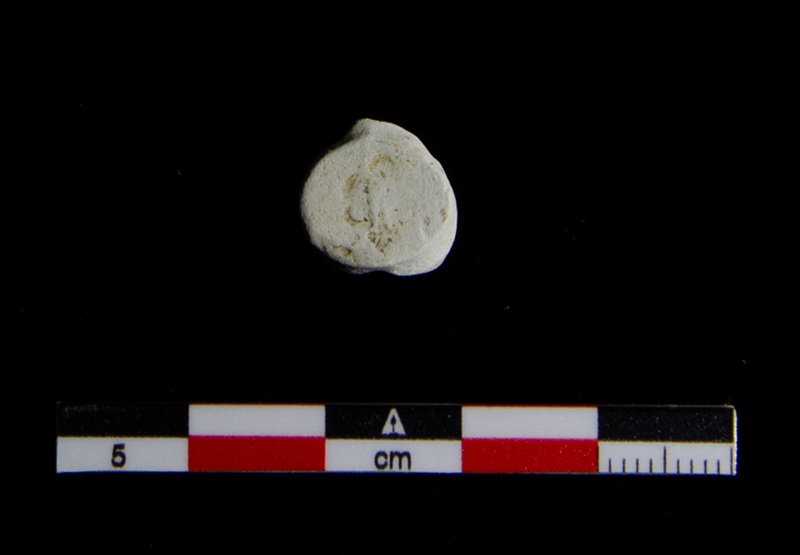

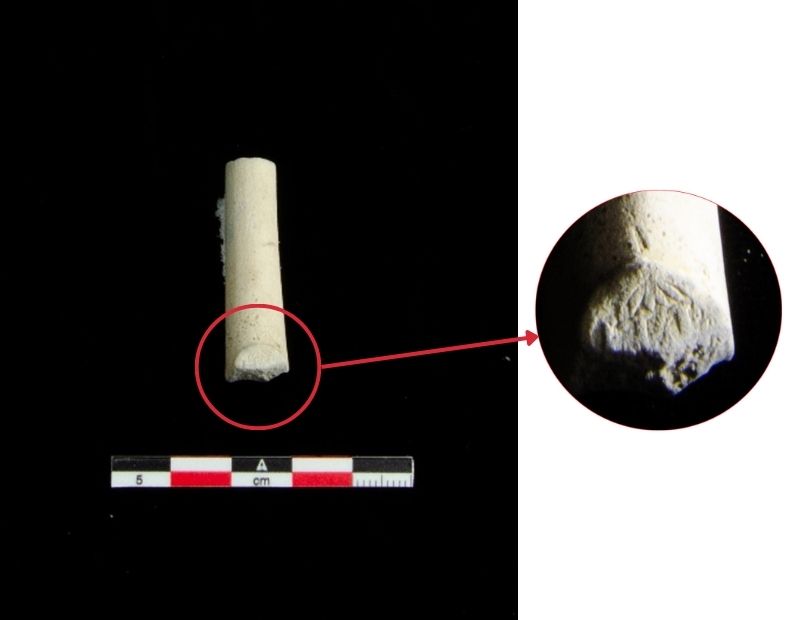

Going into this internship, I had a basic understanding of historic mid-Atlantic material culture and the importance of different artifacts. I knew that animal bones provide insight into diets, and that ceramics can often reflect the economic status of a group of people. Artifacts in abundance within the collection that quickly grabbed my attention were the white clay tobacco pipes (see Figure 1). These pipes originally had long clay stems that broke easily, often littering the ground with fragments that archaeologists can now study. I wanted to learn more about what these pipes could teach, and I quickly found that even fragmentary pipes could reveal a lot of information. Many of the clay pipes found at the site were made of distinct “white ball”, or Kaolin clay, indicating that they were sourced from Europe. These pipes not only offer knowledge of travel to and trade within the colonies but also provide information which can be used to date the occupation of the site. Changes in smoking trends were evident in the manufacturing of pipes. Over time, pipe stems became longer and the bore through the stem grew narrower, likely due to changes in smoking preferences and the need for a longer pipe to be more durable. As pipe stems changed, so did the style and shape of the bowls. Because of the steady change of bore diameters and pipe bowls, a date can be estimated by analyzing them, mostly done by taking the mean measurement of all the pipe stem bore diameters found at a site (Hume 1969, 297). This method was done on a sample of 56 pipe stem fragments from The Maine that yielded the date of 1642. However, the excavation report notes that this method is only reliable for pipes made after 1680, and that pipe bowls offer a more accurate basis for dating. Based on the pipe bowl shapes found at The Maine, Outlaw notes that none of the bowls were made in a post-1620 style, which places the pipes within a date range more consistent with the date suggested by historic records and other artifacts (Outlaw 1980, 36). While going through the pipes, I found quite a few that were stamped with makers’ marks and I was captivated by the small, intricate designs. Small decorative impressions like these can tell us where a pipe came from or who owned it, and I decided to do more research.

The makers’ marks pictured in this article show an eight-spoke wheel or asterisk (Figure 2), a Tudor rose (Figure 3), and an indeterminate intricate design (Figure 4). I was able to find a comparison to the wheel/asterisk mark on the Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website. While it is not associated with any direct maker, similar marks have been found in other sites around Virginia since the early 17th century (Gaulton 2006). I struggled to find examples of the other two makers’ marks, but I did learn about the styles. According to the Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage, the rose was a popular Dutch mark. This supports Outlaw's hypothesis in the excavation report that, while London had a monopoly on the pipe industry, the pipes at The Maine appeared to be Dutch. This information opens more questions as to why this could be. The other makers’ mark is fragmentary but—based on similar styles—I suspect that, had it been intact, there would be two initials observable on the heel. Another design noted in the excavation report shows a very similar depiction of a makers’ mark with the initials, T H (see Figure 5). Further research could reveal that the initials can be attributed to those of a specific maker. At first, I saw these marks as merely fun decorations; I understand now that such small impressions can hold a wealth of information on the people who made and owned these pipes and could open avenues for future study.

While tobacco pipes consisted of only a fraction of the artifacts excavated from The Maine, they offer a good example of how archaeologists can use everyday objects to learn more about a site and the people who lived there. Throughout my summer as a collections intern at DHR, I found myself constantly learning new things, whether it was from studying and asking questions or just observing the people around me who offered guidance and inspiration. The experiences and knowledge that I took away from The Maine and DHR will go forward with me into my undergraduate studies and wherever my passion for collections and archaeology may take me.

Bibliography

Gaulton, Barry. “17th and 18th Century Marked Clay Tobacco Pipes From Ferryland, NL”. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Last modified February 2006. https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/pipemarks-introduction.php.

Hume, Ivor N. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969.

Outlaw, Alain C. An Interim Report Governor's Land Archaeological District, Excavations: The 1976 Season. Virginia Research Center for Archaeology, 1980.

Outlaw, Merry. " Jamestown and Governor's Land, James City County, Virginia." The Chipstone Foundation. Accessed August 6th, 2025. The Chipstone Foundation.