Caught in a Whirlwind: The Chesapeake Shoreline Survey

A grant from the federal Emergency Supplement to the Historic Preservation Fund (ESHPF) gives archaeologists an opportunity to study and record the effects of two 2018 hurricanes on the archaeological resources of Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay shoreline.

By Brendan Burke | DHR State Underwater Archaeologist

Autumn is a special time of year on the Chesapeake Bay. It’s palpable in every sense when you are out on the wide water. A fresh northeast wind brings a new chill to the air that mobilizes all nature into a determined motion. Wildfowl awaken from their summer somnambulance and regroup into winter flocks. Rattling bugles from moonlit flights of sandhill cranes are matched below by schools of bluefish. Crabs, the beautiful swimmers of the Bay, move to deeper water. The first chill sets into motion millions upon millions of lifeforms in a cyclical seasonal pattern that’s far older than any calendar. Most human residents around the Chesapeake Bay are now insulated, both physically and mentally, by this change in seasonal patterns but for generations, even millennia, people of the Bay were especially attuned to it. One aspect that the cold brings is a change in the direction from which storms arrive, even the type of storm. When the first frost forms on creek-side leaves, hurricane season is past.

Tropical storms and nor’easters are some of the most destructive types of weather events for residents of the Chesapeake Bay, but the most feared—perhaps somewhat unfairly—is the hurricane. Less frequent than tropical lows and strong nor’easters, hurricanes have brought memorable calamity to the Bay. In Virginia we now connect 1693 with the chartering of William & Mary, but a later October storm closed many navigational channels in a region dominated by a reliance on navigable tidal creeks for international trade. In July of 1788, a hurricane pounded up the Chesapeake and took its name from its diarist: George Washington. Six of the ten decades of the 1800s saw hurricanes impact Virginia, notably the Eastern Shore, and exposed Virginia Capes. Ships and mariners alike were hurled ashore to their peril. In 1954, babies in the Chesapeake were named Hazel after a hurricane of the same name became the third and most devastating one to strike the Virginia coast since 1933. The fisheries were devastated, as was a wide swath of the Bay Region.

The same beauty and natural riches that are imperiled by storms in the Bay have tempted shoreline occupation since arrival of the first humans. As a species, humans are resilient and adaptive—frequently co-opting nature to fit our own expectations for better and worse—but our species developed a strong predilection for stability. The trouble arises when desire for consistency in nature is paired with the meeting of land and water. The only constant for coastal areas is change. Monolithic coastlines of seemingly immutable stone erode and bow to a pounding surf. Likewise, the sand and mud shores of the Chesapeake Bay throb transgressively and regressively to many powerful global forces, even to extraterrestrial forces such as a great meteor strike some thirty-five million years ago.

Archaeologists studying the Chesapeake Bay, whether focused on cultures hundreds or thousands of years old, must study patterns of change along the Bay’s shoreline. So many of our archaeological sites are shoreside, the same way that today’s population prefers to occupy the fringe areas along our rivers, streams, and even the open Bay itself. When dramatic events such as a hurricane pass, sometimes funding opportunities are left in their wake, such as in the case of Hurricane Sandy. The October 2012 storm passed close by the Bay, bringing storm surge and damaging winds to the region. Near the mouth of Delaware Bay, it made a disastrous left hook and charged inland. You may remember scenes from New York City as the more powerful right side of the storm drove water deep into the city and flooded the subway system. As a result of the damage, the National Park Service (NPS) administered $47.5 million as part of an Emergency Supplement to the Historic Preservation Fund (ESHPF). Such pulses of money often follow recognized disasters and are intended to assist with both restoration of affected historic properties as well as addressing planning needs for affected areas. One such project was undertaken in Virginia by the Longwood Institute of Archaeology (IoA), which worked as a consultant to the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). The resulting shoreline study created a probability model for various areas along Virginia’s western shore of the Chesapeake.The predictive model created a framework for locating the junction for highly erosional zones and the likelihood for the presence of archaeological sites.

While probability models can be powerful tools, they are best trusted, refined, and deployed as management tools only after testing. When the NPS released a round of ESHPF funding after hurricanes Florence (September 2018) and Michael (October 2018), an opportunity to test the Shoreline Model arose. With funding available, DHR contracted a test of the model.

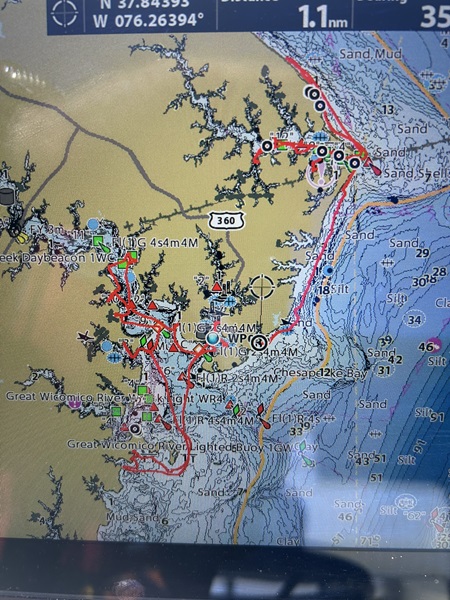

A team from DATA Investigations, LLC, and Dominion Research Group, LLC, began the process of model testing, both on paper and in the field. Currently DHR is assisting with technical aspects of the research as model testing can (and should be) a fluid process of responding to field conditions and the analytical framework. Four areas of Virginia’s Tidewater region were chosen, each with a ten-mile diameter circle of interest. The focus points include Lewisetta, Reedville, Deltaville, and Irvington. Within the areas, roughly 240 points of interest were derived from the Longwood IoA study and selected for field visits. The rationale for area selection was based on variability of shoreline exposure, density of current habitation, shoreline armoring, and known archaeological site preponderance. A short on-land test was conducted in 2024, funded by DHR’s Threatened Sites Grant program, to field-verify the inland components of several sites, but the 2025 test incorporates a much broader geographic test of the IoA predictive model. The basic concept for the IoA model was to pair shoreline erosion potential with the likelihood of archaeological sites based on landform and other characteristics of Pre-Contact site location. The meat of the current survey consists of additional GIS processing of the model and field verification of erosion and site presence.

At present, the fieldwork for this project is underway but a lot of data is coming in. Some areas fall into the model very well, others not as much. Results of this study are determined to refine the model and provide an updated, more reliably ability for site probability and shoreline erosional activity. Weather permitting, survey will conclude by the end of 2025 and the results will be processed over the winter. The most valuable goal of the project is to learn how various areas of the Bay react, and have reacted, to natural erosional forces and how that change threatens both known and unknown archaeological resources. Results should indicate preservation priorities for resource managers.

Much of the fieldwork takes place during chilly mornings and blustery afternoons, but the rewards are plentiful. Rafts of swans, peach-colored sunsets, and swirls of fall leaves on the water are constant reminders of the Bay’s natural beauty. With few exceptions, survey occurs from the water where the survey boat can prowl the shoals and shoreline to examine dynamic erosional patterns and what resources have been affected. If you see a teal-colored skiff skirting the shoreline like a clapper rail, it may be the survey team. As Virginia’s state underwater archaeologist, joining this fieldwork has been an excellent experience that allows me to get to know the Bay better. Unlike other projects where a single site is the focus and time on the water is more of a commute, the Shoreline Survey requires depth of time in the field that reveals nuance and subtle patterns. Watermen and our ancestors on the Bay knew this. To share that same experience is invaluable.