Alice Boucher of Colonial Virginia’s Eastern Shore: Part II

We revisit the story of Alice Boucher, a widow who lived in Virginia's Eastern Shore during the 17th century, after our archaeologist for the eastern region recovered artifacts from what may be the site of Boucher's former home.

By Michael Clem | DHR Archaeologist for Virginia’s Eastern Region

Last February I wrote a piece about Alice Boucher. Alice was a widow who raised her children in Accomack County on Virginia’s Eastern Shore in the last half of the 17th century. She experienced several encounters with the court system and appears seven times in the court order books over a nine-year period, between 1663 and 1672. After that, I lost track of her in both the Northampton and Accomack County records. At the conclusion of the first part of the story about Alice, I conducted some research in an attempt to find where she might have lived. Several clues were given about the location in the records of her court encounters. Some clues were also given in her husband’s court encounters, as well, in the decade before his death. In the end I had enough to allow me to try to find her home site. Here’s the ending to the story I wrote back in February:

After studying Alice’s life, I began a search for the possible location of her home. I attempted to find the oldest map of the area that features the area of Hack’s Neck, and I had to rely on relatively recent 20th-century United States Geological Survey (USGS) topographic maps as well as old nautical charts. I studied these sources and found an area that fits the description given by William Boucher in his testimony about the pig. The area, consisting of mostly swamp, is located by a branch (creek) where William had said his house stood. We know from the initial lease that the property was 100 acres, and that William was required to plant 50 apple trees. On the maps, I followed various indicators of property boundaries, such as tree lines and ditches. I also looked for swampland along a creek. I then checked DHR’s site records and found an entry for a site that is on the edge of a parcel containing a 100-acre field. According to DHR’s records, this site dates to approximately the third quarter of the 17th century, based on the artifacts recovered there. The site was recorded by a passerby traveling on a boat. They had found artifacts eroding from the shoreline of a creek that bears a version of Alice’s name.

After conducting some research into tax records, I found the owner of the property. A retiree who lives outside of Virginia, he told me that he visits the property from time to time. I mentioned the story of Alice to him and described the site’s location. He responded, “Oh, you mean up where the old crabapple trees are growing?” Old apple orchards left to re-seed on their own will, over time, revert to yielding smaller apples that have little resemblance to the original parent variety. Have we found the location of Alice’s home, where William planted 50 apple trees and where her infant son was laid to rest more than 350 years ago? Where she and her children worked so hard to survive?

Swampy conditions exacerbated by inclement weather waylaid several planned trips to examine the site this winter. As warmer months approach, joined by a bit of luck—and possibly a kayak—I’m hopeful we’ll get there.

In the end, I was finally able to go visit the property. I met the owner and left my truck by the entrance gate and we took his vehicle. He drove his old Suburban across bumpy farm roads, through deep muddy puddles and around downed branches. A storm had come through a few days before and left a mess. I was feeling anxious about the condition of the site along the shore. Would it be gone? Would the waves and tides have uncovered more of it, or buried it? I’ve noticed sites on the shore can be exposed one week and be obscured by sand deposits the next. It all depends on the whims of nature. The property owner was able to drive us surprisingly close to the site. Up until this point my only view of the area was through USGS Topo maps and satellite images. Getting boots on the ground here eased some of my worries. The site location was a very short walk away and looked relatively stable, at least at first.

We walked the short distance to the shoreline and, with our rubber boots on, waded in calf high. Eyes on the water and on the small beach, we waded south at first and immediately noticed a number of bricks scattered along the waterline. There were also glass shards and fragments of various types of pottery. After a few minutes of examination and wading in too deep, it was evident that this was a much later site. The bricks were quite uniform in size, well formed, and highly fired, as if in a professional kiln. Such solid and well-made bricks would not have been found on the shore in the mid-17th century, when bricks were hand-made and irregular and featured a great deal of variation in quality; they would have likely been made on-site by someone with limited knowledge or experience. Along with the bricks, the pottery that I noticed here consisted primarily of white tableware of a variety that was not available until the 1820s or so. There were also some red-bodied utilitarian ceramic fragments that were not a type that would have been found during Alice’s time. This was clearly a site dating to the 19th century. I was disappointed and sloshed in my water-filled boots up the shore to empty them before heading northward.

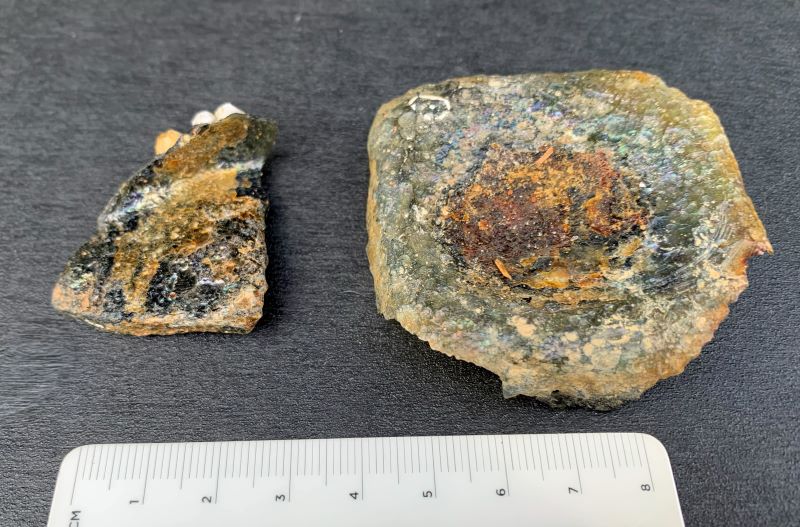

The north side was broken into large and small clumps of seagrass and dead tree stumps. It was clear that the tides and the westerly winds had pushed the saltwater further up into the marsh here, killing the last of the shoreline trees along this stretch. After some rough walking through muddy areas and crossing some uneven clumps, we came to a small intact stretch of sandy shoreline. It was here that our luck changed. The first thing I saw was a scatter of small, friable brick fragments. No complete bricks or even large pieces, but soft red clumps of red, low-fired clay. These were clearly bricks that had dissolved and been beaten by the waves over time. Along with the brick pieces I saw a few fragments of utilitarian pottery. Pottery is one of the most useful tools to an archaeologist for dating a site—at least to a general period—but sometimes it can link a site to a very tight timeframe. Some pottery types are short lived, often due to changing trends, while others last for longer periods due to their useful design and low cost. The finds here included various types of red-bodied wares with either black or brownish glaze. These are common brick types that boast a long life, running throughout the colonial and post-colonial periods. Fortunately, there were also some North Devon gravel-tempered and non-gravel-tempered fragments. There were some Buckley-ware fragments as well. These materials are clearly items that would have been found in most colonial households of the time. They had a relatively solid period of use that spanned the 17th century, and diminished in use through the 18th century, until they nearly vanished from sites by the latter half century.

Also found here was a small fragment of a square-sided bottle and a small bottle base, both of which may be identified as part of what is known as a case bottle. Early 17th-century glass blowers found that it was easier to blow bottles into square shapes and put 12 in a wooden case for shipping. Hence the name. The case bottle featured the most common shape found through the first half of the 17th century, when they were used to hold almost any kind of liquid. Case bottles would have been reused multiple times for various purposes. People certainly didn’t throw out a good bottle very often. While most bottles by Alice’s time would have been more rounded and globular in shape, it’s certainly no surprise to find an older survivor from earlier times.

The next class of artifact that we found at the site was related to tobacco-smoking. In the waterline, over a small stretch of sand, and mixed in with the ceramic fragments, I found four tobacco pipe fragments. One of them also included part of the pipe bowl. Interestingly, all four were made of local clay. Three in the style often associated with Native American pipe manufacturing, made of local red clays and a courser finish. One was also of Virginia clay, but a lighter version, with a less grainy texture and a burnished finish. This one looked more like the pipes crafted by makers along the James River.

In all, this isn’t much to go on. A handful of items found on an eroding beach doesn’t sound like much. Normally this kind of find wouldn’t set off any major alarms. However, in this case, given what we know and the clues from the courthouse documents, this site seems promising. The artifacts found at this spot are not a mix of items from different centuries. They all relate to a very narrow time period within the mid- to later part of the 17th century. They all speak of a domestic site that featured some brick, cooking and storage vessels, and pipe-smoking. This find isn’t just casual discard; it’s the remnants of a home. Unfortunately I suspect that much—if not all—of the site is gone. Lost to the waves. This spot would have looked very different 350 years ago. I hope to get back there soon and to do some more reconnaissance work. You never know what you might find.

In the meantime, I’ll be doing more research into the Boucher family history. After the last article was published, I was contacted by an individual who grew up in Virginia but had moved away since. This person found that they descended from William Boucher and had further information that could potentially lead to where Alice and her children went after I lost track of her in the court records of 1672. To follow the records, I’ll need to go to Delaware. Stay tuned.