Swagger, Swing, and Soldiers: The Tart History of Virginia’s Apple Industry

"[Apples]...are living threads that lead directly back to three hundred years of the southern agrarian past.”—Lee Calhoun, 1995.

By Sherry Teal | DHR Project Review Architectural Historian

We all know the sayings, “American as apple pie,” “apple of my eye,” and “an apple a day keeps the doctor away,” but how did apples become so embedded in our language? In the grocery store, the top five types of apples—Red Delicious, Honeycrisp, Granny Smith, Gala, and Golden Delicious—lined up in colorful rows as we enter the produce section are as expected as the squeaky wheel on the shopping cart. Why did this humble pome become the iconic American fruit? As excitement and preparation builds for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next year, you are sure to see apple pie and apple cider front and center at our parades and parties. But did you know there were once thousands upon thousands of varieties? Continue reading and let us know which one you think is the quintessential American apple in the comments.

From Far, Far Away, but Here to Stay

You may be surprised to know that apples aren’t from North America. Crab apples originated here—and American Indians cultivated them long before Europeans came to Atlantic shores—but they are cousins to the popular fruit we know today. The apples that we see at the grocery store and at roadside produce stands originated in central Asia. Apples traveled to Europe on trade routes sometime around 1000 B.C. from Kazakhstan. These early apples found favor with Greek, Etruscan, and British people who recorded them in art and literature (see Figure 2).

In the early 17th century, apples traveled in the hulls of ships with colonist groups that were crossing the Atlantic Ocean. These apples found their way into orchards in what would become the Commonwealth of Virginia (Calhoun, 3). To Europeans, the apple was known as a prolific, relatively easy food to grow and was valued because it could survive the long voyage overseas and keep well in storage cellars during tough winters. Apples would give much-needed nourishment during times of the year when other crops couldn't grow. The British were especially fond of apple cider and brought their passion for it with them to the colonies (Calhoun, 3).

Apples were so important to Colonial American settlers that many, if not most, land grants required owners to have orchards to receive land from the King of England. Most of the grants were given to wealthy investors who either used forced labor to farm the land and tend the orchards or divided the land out to tenants for lease (Calhoun, 3). An orchard signified success. If the settlers had an orchard, the grantors knew the small farmers would have a better chance of surviving and in turn ensure a profit for the investors. There was usually a stipulation that the tenants must keep their orchards fenced, pruned, and the trees planted a certain distance apart to encourage the health of their crop. George Washington required his tenants to plant two hundred apple trees and peach trees to receive land. In Westmoreland County in 1686, one owner alone, Colonel William Fitzhugh, had 2,500 apple trees (Calhoun, 3).

In 1741, a lease between Charles Carter of King George County and William Johnson of Orange County outlined the responsibilities of the tenant. Johnson’s rent would be 530 pounds of tobacco and he would agree to build a “…dwelling house 20 feet long and 16 feet wide, with inside chimney…after the manner of Virginia buildings, and agrees to further plant an orchard of 100 apple trees and 100 peach trees and not to work more than three servants or slaves on the tenement” (Culpeper Historical Society, 77). Through this lease agreement, we not only see how apple orchards were a main part of the process of settlement, but we also see a standardization of early vernacular architecture in Virginia.

A Bit About Grafting

Why is grafting important? In short, predictability. Apple blossoms contain the stamen (male cells) and the pistil (female cells). Most apple varieties must be fertilized by orchard bees, moths, or other insects, but only pollen from other apple tree varieties will produce fruit. Each apple seed, in every apple, is unique because the apple blossom can be fertilized by multiple insects carrying pollen from multiple, unknown trees. Farmers need to be able to plan what products they will make after harvest or which apple they will sell to buyers (Calhoun, xiv). A cider apple’s qualities are different than that of a pie apple. How can an orchardist get the same apple variety every time? The secret is grafting. Saplings, or suckers, that sprout from the base of a tree will always produce the same qualities as the apples from that mother tree. Farmers take a live root from the tree they want and affix it in a small hole to a "foster" tree (Calhoun, xvi). Grafting allows growers the ability to predict which apple they will get, and therefore, be able to plan what to sell.

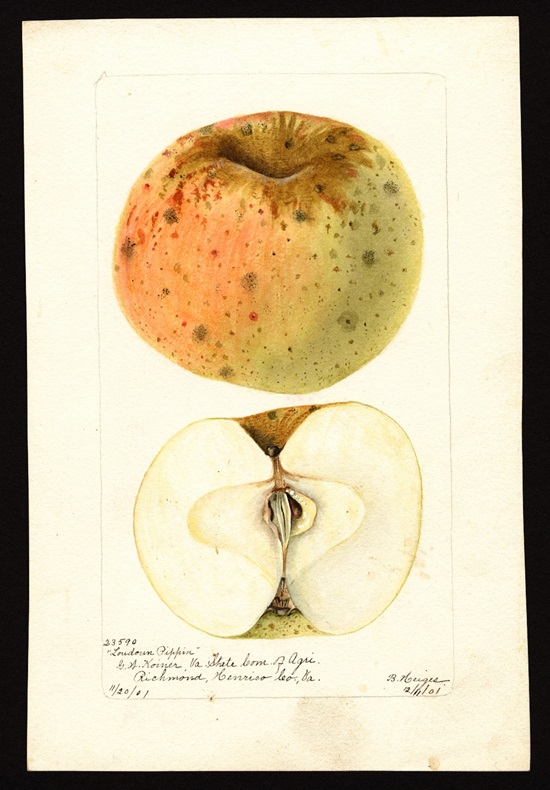

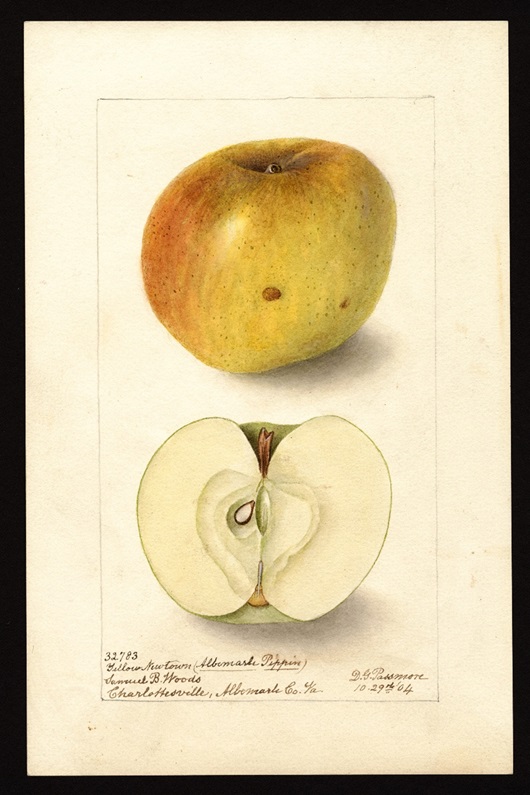

In 1725, a professor at William & Mary College observed, "the Apple trees are raised from the seed" and were extremely diversified (Calhoun, 4). It wasn't until 1750 that grafting apple trees became a common practice and an integral part of apple production (Calhoun, 4). In 1755, Dr. Thomas Walker came to Albemarle County and planted an apple tree on Mildred Merriwether’s farm at North Garden. By the early 1800s, grafting the Albemarle Pippin (Figure 3), also known as the Newtown, or Yellow Newtown, allowed it to be widely distributed and exported.

The Apple of My Black Eye

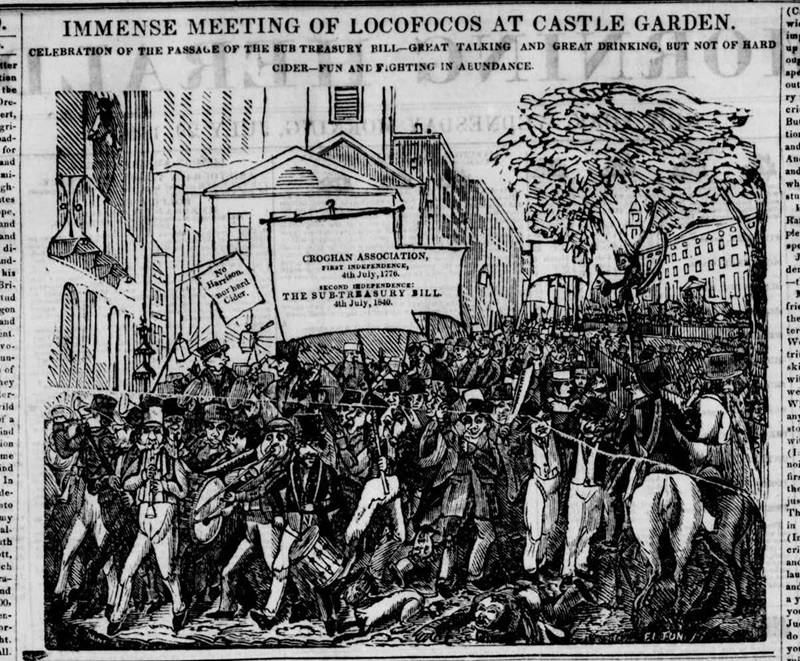

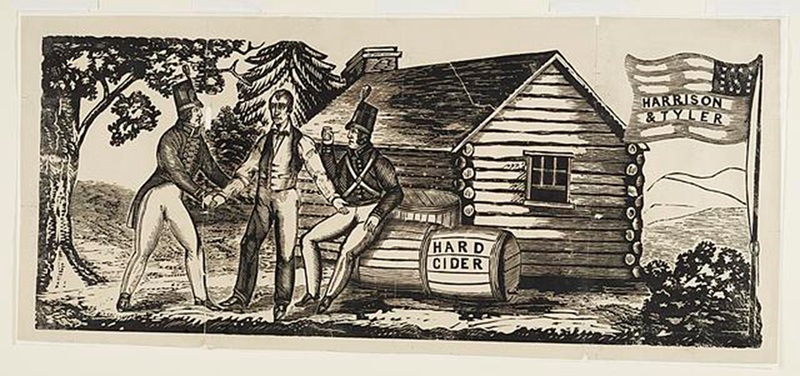

Apples have been the center of historic arguments that sometimes led to fisticuffs (see Figure 4)! In the 1840 presidential election, candidate William Henry Harrison and his running mate John Tyler launched an ‘every man’ campaign against the incumbent Martin Van Buren. The election was lively and both candidates engaged in ‘mudslinging.’ Harrison fostered his image as that of an everyday American—not one of the social elites—to gain popularity and win the vote. Even though his family was wealthier than Van Buren’s, he pursued this “blue collar” image in earnest. He did this by saying he would rather ‘drink hard cider and live in a log cabin’ than live luxuriously like his opponent (Figure 5). Henry Clay, who was born in Hanover County, Virginia, and later became a congressman in Kentucky, was one of Harrison’s supporters. Henry Clay became so recognized for his speeches about Harrison and his ‘Log Cabin and Hard Cider’ image for the campaign, that a cider apple was eventually named for him (see Figure 6) (National Park Service, n.d.). During the election, large gatherings of both parties, some drunk on cider and some drunk on whiskey, would incite brawls, a few of which resulted in black eyes.

Nineteenth-century debates about certain apples and their associations with famous historic figures caused vigorous arguments between agriculturists well into the mid-20th century. The disagreement between growers about an Albemarle County apple and its historic relationship with the Queen of England went unresolved for over a century. Agriculturists in a 1960s agricultural publication reported a story handed down to them from the 1830s. They retell the tale of when President Martin Van Buren appointed Andrew Stevenson to be a U.S. Minister to the Court of Saint James in London. Stevenson was reported to have had seven barrels of Albemarle County’s finest Pippin apples shipped to him so that he could present them to the newly crowned Queen Victoria. Growers in Pennsylvania did not agree that the Albemarle Pippin was the first apple grown in the colonies to be introduced to England, and insisted it was Benjamin Franklin who introduced the Northern Pippin to England (Virginia Record, 17, 18).

There was also a hearty debate over whether Martha Washington baked cherry pie or apple pie for George. The Virginia Apple Commission sought to “Set the Record Straight” in an article in the Virginia Record. The commission insisted that Martha only had apple pie recipes in her recipe book—not cherry (Virginia Record, 8). The city of Winchester celebrates George Washington’s apple connection with art on its main street (Figure 7).

Apple Swagger

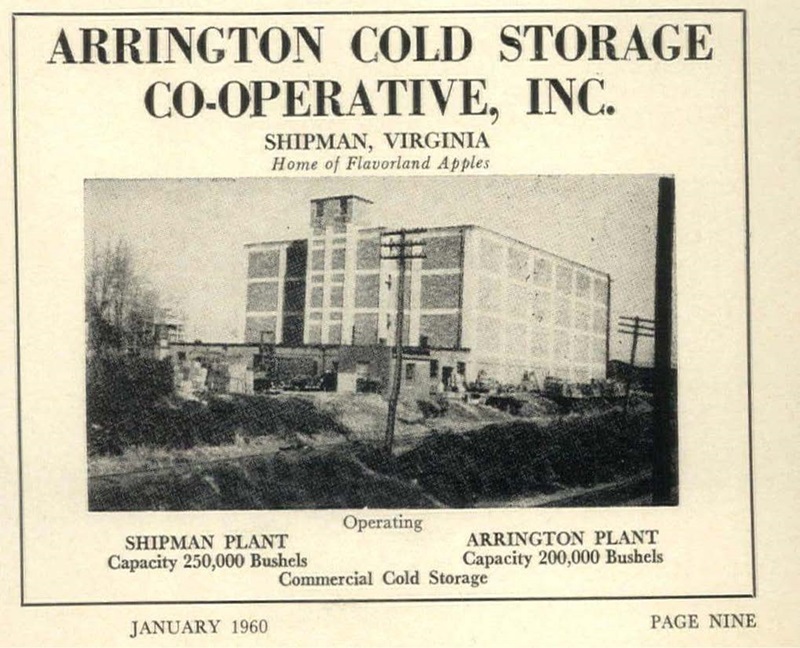

In Virginia in the 1850s, the Shenandoah Valley was known for its apple orchards, but the apple industry centered around Chesapeake Bay, mostly because of the access to water trade routes. As the 19th century came to a close and railroads made their way into the interior part of the country, apple orchards on the east coast of Virginia waned and new orchards in the western mountains increased (Calhoun, 11). By 1890, Virginia had attracted an investment that caused a “delirium of apple planting” (Calhoun, 12). This speculative planting of millions of trees caused a crash in apple prices at the turn of the century (Calhoun, 12). When the apple industry rebounded, growers tried to stand out from their competitors with interesting, and sometimes ostentatious, names.

Apple species became so numerous that the names that growers chose for them ranged widely. Names could represent where the apple was grown; be named for a family member; or describe what they could best be used for, like storing, making applesauce, or cider (Calhoun, 31-33). Growers tried to think of ways to make their apples more desirable, and choosing a name was serious business that eventually, at times, involved lawsuits. Magnum Bonum, Nickajack, Accordian, Aunt Rachel, and the showy Baltimore Monstrous Pippin were all names used for apple varieties. Orchard owners also started to use large, colorful billboards on the side of highways to attract attention and to boast that their apples were the best. These billboards developed from being finely illustrated and detailed in the 1890s, to being stylized with bold colors featuring new shipping technologies, machinery, or the size of their orchards in the 1920s and 1930s (Rich, 2012) (see Figure 8).

Living and Working in Virginia’s Apple Country

Before refrigeration apples perfumed Virginia's rural houses by being stored in the coolest rooms. On winter mornings, their aroma would sugar the senses with their sweetness while sausage was cooking in cast iron (Calhoun, xiii). Apples continued to be popular through the 20th century for rural Americans because they stored well through the winter and they had so many uses. People could eat them, but they could also make cider; dry them to eat later; use their pectin to make jellies and jams; give the leftovers to livestock; and, best of all, make desserts to wow their neighbors. The process of storing and drying apples changed little over time in Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains. In 1935, lining apples on screens or on a tin roof in the Shenandoah Valley was a common practice that continued into the 1980s in the southern range near Ararat (see Figures 9 and 10).

Thousands of acres of apple orchards in Virginia demanded a large labor force to pick them. Apple season, being only a few months long between August and October, gave workers three months to pick millions of apples. Pickers moved from place to place as the season grew shorter, chasing the ripening of the apples. In the 1940s, their work took them across Chesapeake Bay from Virginia into Delaware. The apple industry in Virginia was a physically demanding, cross-country experience for laborers (Figure 11).

Swing Time and The Big Apple

The apple in American culture inspired more than raucous presidential debates and arguments about an apple’s origin. It also inspired slang terms and music. The nickname to describe New York, The Big Apple, was first used in the 1920s by John J. Fitz Gerald, a sports reporter for the Morning Telegraph. The Big Apple was slang for a sure bet in horse racing or to describe a circuit of races with good winnings for gamblers. Fitz Gerald wrote, “The Big Apple, the dream of every lad that ever threw a leg over a thoroughbred and the goal of all horsemen. There’s only one Big Apple. That’s New York.” The term was indicative of success and a big win (Nigro, 2015). Jazz Age slang spawned other terms in the 1930s and 1940s and in big band music, or swing music. The swing instrumental, “Stealin’ Apples,” was a popular tune and was included in the 1948 movie, A Song is Born. Andy Razaf and Fats Waller wrote the song, and, in 1936, Fletcher Henderson and his orchestra recorded the tune for the first time.

Mom and Apple Pie

At the outbreak of World War II, the apple was iconized in one of American culture’s most recognizable sayings. When Queen Elizabeth II was thought to have coined the famous phrase, “as American as apple pie,” the words provided us with a metaphor for American perseverance and independence because the first settlers depended upon apples to survive. Apples gave us the fuel to fight British rule. However—and sorry Queen Elizabeth II—the phrase was first popularized during World War II by American soldiers leaving to fight against the Nazis and other enemies of the United States after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. When newspaper journalists would ask them, “Why are you enlisting?” soldiers often answered, “for mom and apple pie.” (New York Times, 1942) (Figure 14).

The phrase reflected our American roots: the trees bound to the land through immigration, and the use of the fruit steeped in our culture through neighborly connection. Apple pie and all its variations reflect our shared American experience. All of our forefathers and mothers arrived in this country (or were here before the Europeans came) and tended apple orchards. We can see and taste our shared culture transmitted through time in apple names like Cullasaga, Nansemond, Dutch Mignonne, and Pomme d’Or. We learned varieties from our neighbors and shared them during lean times. Our ancestors took a great dessert from Europe and made it their own for everyone to enjoy. As we celebrate the coming of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, we hope you remember the humble apple and how it helped to shape our nation’s history.

Bibliography

Calhoun, Creighton Lee. Old Southern Apples, A Comprehensive History and Description of Varieties for Collectors, Growers, and Fruit Enthusiasts. Revised and Expanded Edition. The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, Blacksburg, Virginia, 1995, First Edition 1995. Chelsea Green Publishing Company, White River Junction, VT, 2010.

Culpeper Historical Society. “An 18th Century Perspective: Culpeper County,” Culpeper Historical Society. Culpeper, Virginia, 1976.

Delano, Jack (photographer). “Migratory agricultural workers at the Little Creek end of the Norfolk-Cape Charles ferry. They are going to Bridgeville, Delaware to pick apples,” 1940. Source Collection: Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection Library of Congress.

Gruenfeld, George. Paul Hill. Yellow Newton. Pomiferous. pomiferous.com/applebyname/yellow-newtown-pippin-id-6801 (2016-2021). Accessed August 15, 2025.

Heiges, Bertha. Malus domestica: Loudoun Pippin. USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection.

Highsmith, Carol M. “Apples are big in Winchester in the midst of western Virginia's thriving orchards.” 2010, published 2019. Source collection Carol M. Highsmith Archive. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Accessed August 15, 2025. https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print .

Mullen, Patrick and Terry Eiler (photographer). “Jess Hatcher drying apples, Ararat, Virginia.” Source Collection: Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project collection, 1977-1981 (AFC 1982/009). American Folklife Center.

Nigro, Carmen. “Why Is New York City Called the Big Apple?” Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy. Accessed August 16, 2025. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2015/03/11/nyc-big-apple.

National Park Service, “The Election of 1840.” Martin Van Buren National Historic Site, New York, webpage. No date. Accessed August 14, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/mava/learn/historyculture/the-election-of-1840.htm.

Rich, Sarah C. “Airships and Oranges: The Commercial Art of the Second Gold Rush,” Smithsonian Magazine, Washington, D.C., March 1, 2012.

Roswell Page, Jr. “A Saga of Virginia Apples.” Clifford Dowdey, ed. Virginia Record, Richmond VA. State Capital Publishing. 1960.

Rothstein, Arthur (photographer). “Spreading out apples to dry, Nicholson Hollow. Shenandoah National Park, Virginia.” 1935. Source Collection: Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Steadman, Royal Charles. “Henry Clay.” USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection.

Unknown artist, "Harrison & Tyler campaign emblem,” 1840. Source Collection: American cartoon print filing series, Library of Congress.

Unknown artist. Hercules stealing the Golden Apples from the Hesperides. Detail of The Twelve Labours Roman mosaic from Llíria, Spain. Museo Arqueológica Nacional, Madrid. Courtesy of the Ministerio de Cultura, v52.2, NIPO: 551-09-050-6. https://ceres.mcu.es/pages/Viewer?accion=4&Museo=MAN&AMuseo=MAN&Ninv=38315BIS&txt_id_imagen=3.