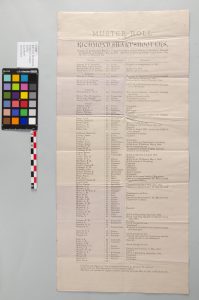

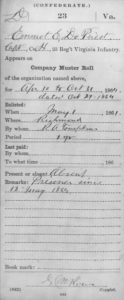

Cornerstone Contributions: The Richmond Sharpshooters, Company H, 23rd Virginia Infantry Confederate Veteran's Muster Roll

The Donor

Who deposited this item in the cornerstone box? Why did he deposit it? George T. Mattern, a private in Company H of the 23rd Virginia

Regiment, placed the muster roll in the cornerstone box. His service records indicate he enlisted in May 1861, was captured in 1864, and released from confinement at Fort Delaware after taking an oath to not take up arms against the US government in May of 1865 (https://www.fold3.com/ ). He does not appear to have been involved with Confederate Veteran organizations but it is known that he served as a police officer during the unveiling of the Lee Monument (SHSP 1889:257). Only George Mattern knows the reasons why he deposited his unit muster roll in the cornerstone box, but perhaps he thought it fitting since his unit was part of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

The 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment

The 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment was organized early in the war and consisted of ten companies. One company was from the city of Richmond (Company H) and the other nine companies were from Louisa, Amelia, Goochland, Prince Edward, Charlotte and Halifax counties. Company H was one of ten companies (A-K) that were a part of the 23rd Virginia Infantry that enlisted for a year in the spring of 1861.

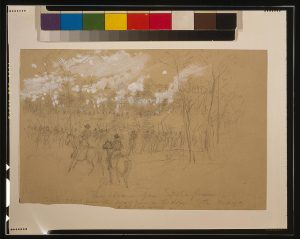

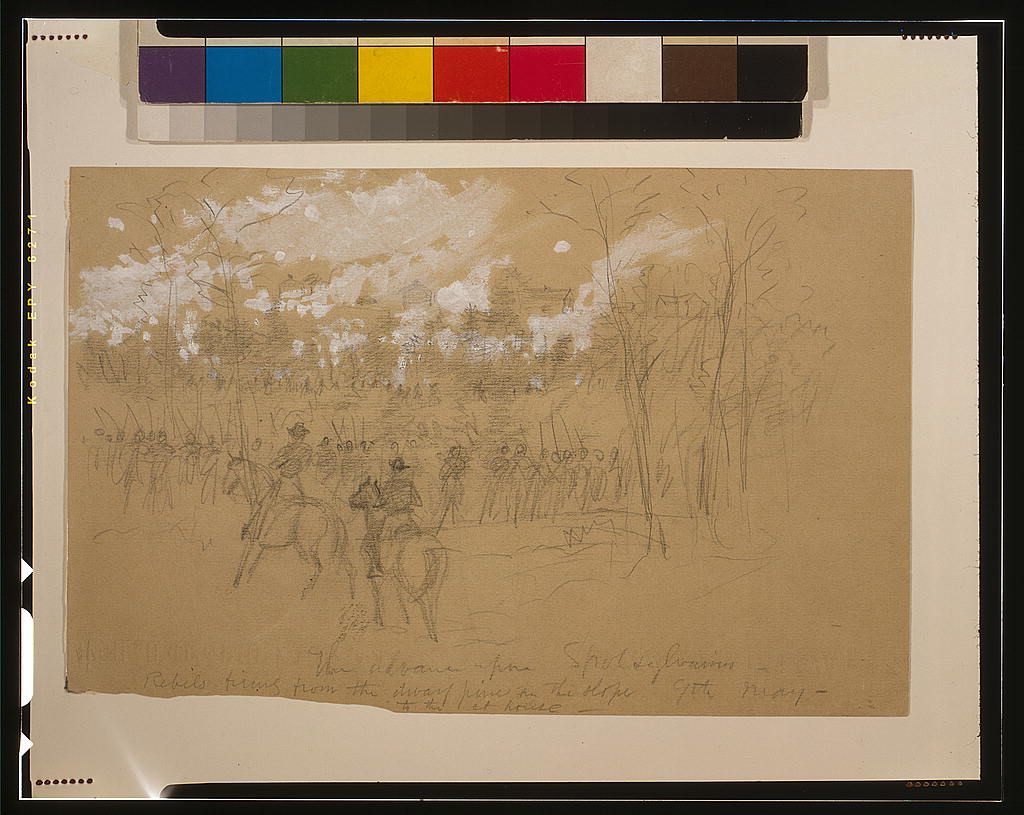

The regiment was actively engaged in several campaigns until they surrendered at Appomattox Court House at the close of the war in April 1865 (Rankin 1985). The 23rd fought in several engagements and sustained casualties in battles fought in the Eastern Theater including Corrick's Ford, Kernstown, McDowell, Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Gettysburg, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Chancellorsville and Petersburg (Rankin 1985).

The Post Civil War Muster Roll

Civil War era company muster rolls are informative documents that contain information on the names of the men, their rank, when and where they enlisted, when they were last paid, where they are currently located, and the name of the commanding officer. Each roll contains a remarks section that is used to indicate if the soldier has been killed in battle (and if so, in what battle), wounded, AWOL, in prison, sick, deserted or furloughed.

The Richmond Sharpshooters (Company H), 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment muster roll is a post-war roll of the unit compiled by Confederate Veterans from war records. This muster roll contains information about the soldiers themselves along with their service history and may have been printed for a special occasion, possibly laying of the cornerstone for the Lee Monument.

The Men of Company H

The post Civil War muster roll lists the original 81 members of the unit when they mustered into service on May 16, 1861. What is known about these men?

Most soldiers were 19 or 20 years old and their ages ranged from 18-35. The average age of a soldier was 21 years. Two soldiers who stated their age as 18 at enlistment were discharged after they were found to be 17 and another soldier was discharged as being too old because the Confederate Conscription Act of 1862 only allowed men up to the age of 35 to serve.

The men in the Richmond Sharpshooters had diverse occupations. Of the original 81 members of the unit, 32 different occupations are represented. The greatest number were carpenters followed by painters, clerks , machinists, printers, blacksmiths, coopers, famers, coach trimmers, tobacconists, sailors, bartenders, bakers and locksmiths. Other occupations represented by soldiers include mechanic, steward, cigar maker, file cutter, collier, cabinet maker, baker, coach maker, shoemaker, merchant, plumber, tailor, confectioner, tinner, teamster, boatman, butcher and school boy. Other companies in the 23rd Virginia Infantry were from rural areas comprising mostly farmers.

Their Wartime Experience

The men of Company H saw the elephant. The term "seeing the elephant" or "seeing the monkey show" were idioms used by Civil War soldiers to describe the experience of combat (Barnett 2021). These colorful expressions originated from attending circus events featuring never before seen exotic animals when they were boys or adolescents.

Some survived almost four years of war and privation. Many were wounded (WIA). Some were killed-in-action (KIA). Others deserted. Many fell ill, suffered disabilities, and received medical discharges. Several were taken as prisoners-of-war (POW) and held in Union POW camps. While prisoner-of-war, one member of company H, was used as a human shield and later became known as one of the "Immortal 600" (Ogden 1911, Joslyn 1995, 2008, Stokes 2013).

As is always the case with Civil War sources, the written accounts differ. The post Civil War muster roll and modern day research conducted over one-hundred years later by a historian (Rankin 1985) do not always agree. Although the post Civil War muster roll states at the bottom that the information was obtained from war records, flawed memories compounded by personal bias, post-traumatic stress and the phenomenon known as the "fog of war" may have been at play when the roll was compiled.

The Richmond Sharpshooters muster roll lists thirteen original members of the company that were killed in action (KIA) however, research by Rankin (1985) indicates that only 8 were killed in action or died of wounds received. Four of those listed as KIA on the Veteran's muster roll are listed as captured and one is listed as a deserter in the roster compiled by Rankin. One other member of the unit died of disease in a hospital in Staunton, Virginia.

Over twenty-five, or approximately one-third, of the original members of Company H were discharged for various reasons. Six soldiers are listed on the Veteran's muster roll as having survived wounds received on the battlefield. Some of these soldiers were discharged with medical disabilities. Other soldiers were discharged due to sickness (Rankin 1985). Robert Jarvis, listed as having been dismissed from service on the Veteran's muster roll after been elected as an officer, was relieved of command on the charge of drunkenness (Rankin 1985).

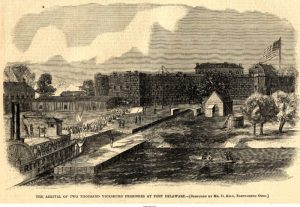

Other soldiers were discharged early in the war after they had been captured and paroled, an action consistent with the terms of their parole but a few reenlisted. Later in the war, when Grant's policy of attrition was applied, Confederate prisoners were no longer exchanged but confined in Union prisoner-of-war camps. Nine were confined at Fort Delaware. Delaware prisoners were not released until May or June of 1865 after they had signed an oath indicating they would no longer take up arms against the US government (Rankin 1985).

The Veteran's muster roll lists eight men as deserters and that number increases when the research conducted by Rankin (1985) is considered. The issue of desertion is clouded in the records as some of those listed as deserters on the Veteran's muster roll are listed as captured in other records. One soldier listed on the Veteran's muster roll earned the distinction of not only being a deserter but also joining the Union army and having been one of "the first to enter Richmond".

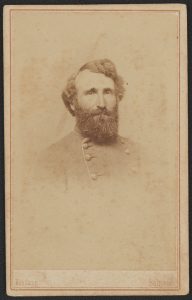

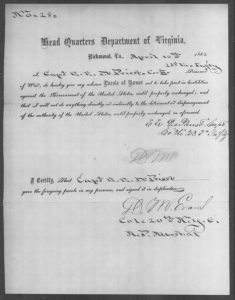

Captain Emmet E. DePriest

Officers up to the rank of Captain in Confederate militia units such as the 23rd VA Infantry were elected by the men of the company. The first three officers listed on the roll were either discharged, resigned, or not reelected. The most junior officer, Emmet E. DePriest, a young, 21 year old, third lieutenant was elected captain in 1862. His service records indicate that he was an able leader but sickly. He was cited for gallantry in 1861 at the action at Carricks Ford (Joslyn 1995:86) but in 1862 he wrote a letter to Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, Christopher Memminger, seeking a job as a clerk due to poor health stating he could not survive another winter campaign (DePriest 1862). He served briefly as a recruiter in 1862, was wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, and suffered from neuralgia in Richmond hospitals in March,1864 (https://www.fold3.com/, Rankin 1985).

DePriest’s future took a dramatic turn when he was captured at Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864. He was held as a prisoner-of-war at Point Lookout then transferred to Fort Delaware in June 1864 (Joslyn 1995). During his confinement, DePriest was sent to Charleston, South Carolina to be used as a human shield along with other Confederate officers known today as the "Immortal 600" (Stokes 2013). This action was ordered by Edwin Stanton, Union Secretary of War, in retaliation for Confederate forces placing 600 Union prisoners in the line of Union artillery firing on Charleston. He was then transferred to Fort Pulaski where fellow prisoners died of dysentery. While he was being transferred back to Fort Delaware in March of 1865, he escaped (Joslyn 1995:86).

The End of Company H and the 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment

Towards the end of the war, both the company and regiment were decimated. The Company H muster roll for November-December 1864 had only six privates listed (History of the 23rd VA). When the 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment evacuated Petersburg on April 2, they retreated westwards. Only fifty-five men of the 23rd Regiment made it to Appomattox Courthouse to surrender with Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

None of the original members of Company H of the 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment were present when what remained of the 23rd regiment surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse in April, 1865. Both the CV muster roll and Rankin's history of the regiment are in agreement that none were paroled at Appomattox. All 81 original members of the company had been killed in action, discharged for various reasons, deserted, transferred to other companies or were still actively held as prisoners-of-war. The remaining members of Company H captured at Spotsylvania Courthouse in 1864 and held in confinement at Fort Delaware were released in May-June of 1865. They all signed a solemn Parole of Honor to no longer "take part in hostilities against the Government of the United States".

Several original members of Company H lived long after the Civil War, including the private that deposited this muster roll in the cornerstone box in 1887.

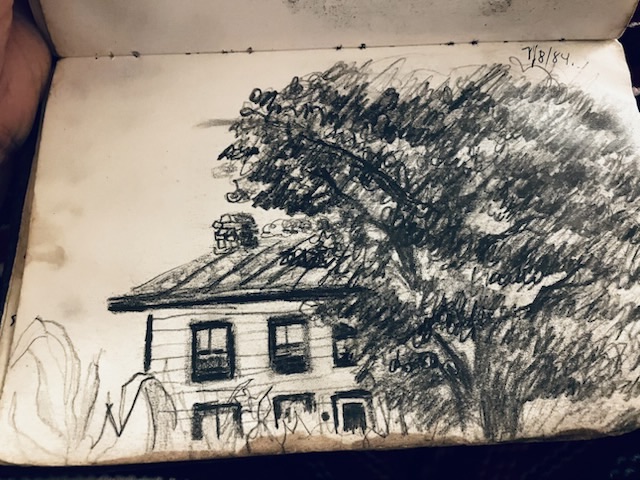

Their captain died in 1903 at age 61 and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia (FindAGrave). Today, the tradition of the 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment is remembered by a reenactor group by the same name that maintains a website with information about their history (Welcome to the 23rd VA).

- Bob Jolley

Archaeologist for the Northern Regional Preservation Office

Department of Historic Resources

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

References

Barnett, Tracy L.

2021 Seeing the Elephant. The Civil War Monitor. Volume 11:4

DePriest, Emmet E.

1862 Letter to Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, Christopher Memminger.

History of the 23rd VA website. Accessed April 4, 2022

Joslyn, Mauriel

1995 The Biographical Roster of the Immortal 600. White Maine Publishing Company, Inc.

2008 Confederate Officers and the United States Prisoner of War Policy. Pelican Publishing.

https://www.fold3.com/. Accessed March 21, 2022

Ogden, Murray J.

1911 The Immortal Six Hundred: A Story of Cruelty to Confederate Prisoners of War. Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company.

Rankin, Thomas M.

1985 23rd Virginia Infantry. H. E. Howard, Inc., Lynchburg, Virginia.

Southern Historical Society Papers

1889 Southern Historical Society Papers: Volume 17.

Stokes, Karen

2013 The Immortal 600: Surviving Charleston and Savannah. The History Press.

Welcome to the 23rd VA website. Accessed April 2, 2022.