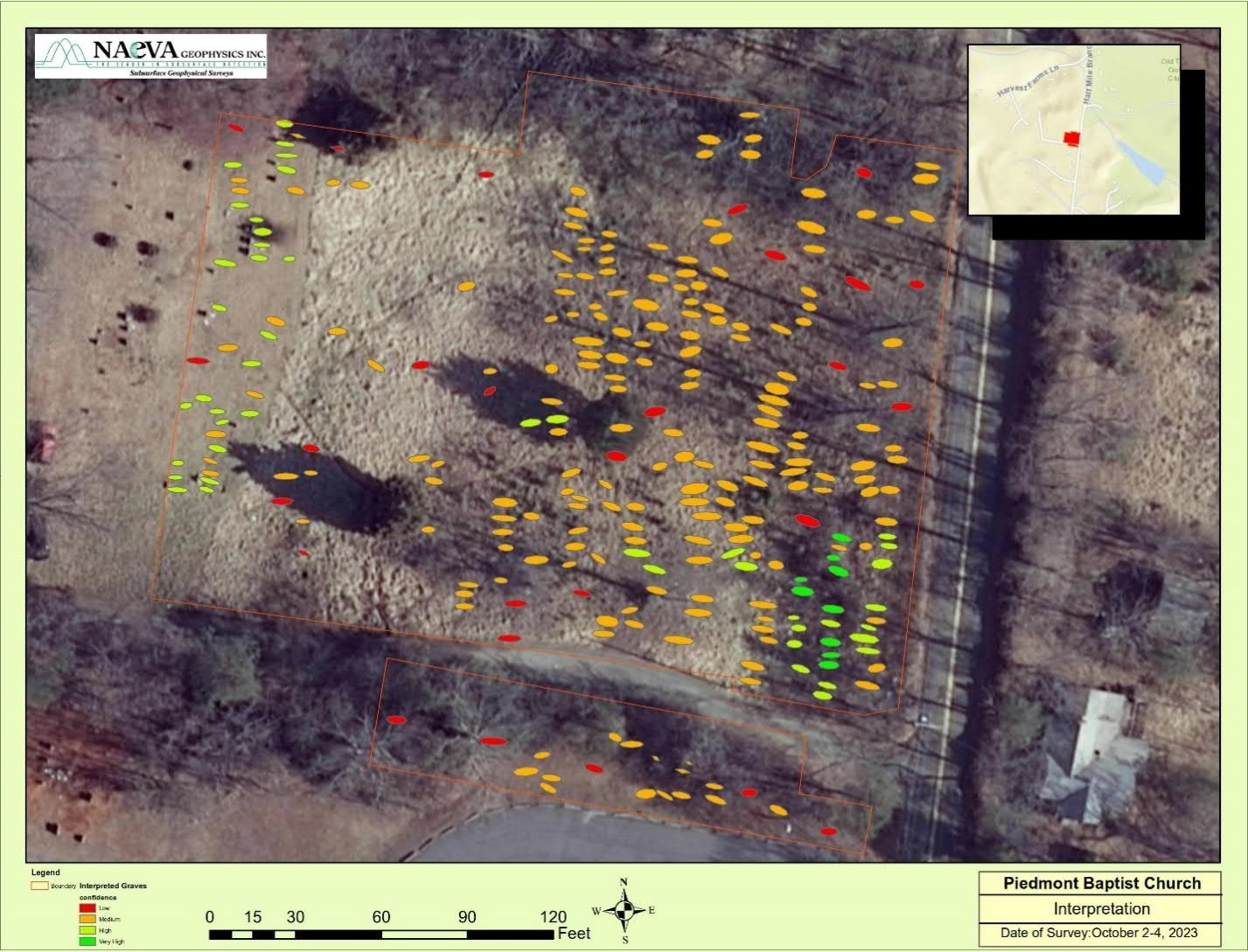

Cornerstone Contributions: The Seal of the Office of the Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office, CSA

A wax impression taken from the Seal of the Adjutant and Inspector General's Office of the Confederate States Army was one of the artifacts recovered from the copper box laid beneath the Lee monument cornerstone. In this blog, we explore the offices of the Adjutant and Inspector Generals and their role in the Confederacy, as well as the wax seal and the man who saved it for posterity.

[Top left photo: This is a wax impression from the seal of the Adjutant and Inspector General's Office of the Confederate States Army. Collected by Capt. John Mayer, who worked within the office, this seal would have been affixed to important documents to indicate they were originals issued from the central office.]

Making It Official: Creating Government, Army, and Credibility

If the pen is mightier than the sword, then perhaps the seal is mightier than the pen. Many documents, even when signed, are not complete without an official seal. The concept of sealing is ancient and still venerated. From notaries to clerks of the court, much of our business is simply not official until it is sealed. When the Confederate States of America sought to gain legitimacy as a political organization in 1861, it created offices that could do the business of the government in rebellion. In many ways, the Confederate government was similar to the United States government. The same was true of the Confederate States Army (CSA).

Formed in February 1861 by the Provisional Confederate Congress, the CSA was mustered in Charleston, S.C., the following month. After its founding, the CSA was largely sidelined by distractions from the war and never expanded to become a real fighting force. Instead, each state organized militia units under the command of its governor. Confederate President Jefferson Davis, a veteran of the U.S. Army, served as Commander in Chief and worked directly with field commanders, such as Gen. Robert E. Lee, to assemble and control the movement of fighting forces. Lee became General in Chief of all Confederate infantry, artillery, and cavalry forces during the final months of the war.

In 1861, the Confederate Army needed a central command structure. It is often said that an army runs on its stomach, but perhaps it is more accurate to say that an army runs on food and ink. As many veterans know, paperwork can be a memorable part of serving your country. Since time immemorial, armies have created mountains of paperwork, often in duplicate or triplicate. The offices of the Adjutant General and the Inspector General thrum, even in peacetime, to keep an army well-ordered and prepared for battle. Let us take a moment to reflect on why these offices are critical to the operation of any fighting force.

Organizing for Victory

The word adjutant—rarely used outside a military context—refers to an administrative assistant, a commissioned officer, or one who serves a higher officer. An Adjutant General is thereby the highest-ranking administrative officer in an army. While the role may not direct troop movements or pull the lanyard on a cannon, the Adjutant General is critical to organizing an armed force.

General orders flow from the Adjutant General's Office. These are the overarching orders that function as an administrative code for officers to consult. General orders cover a wide variety of topics, some of which may even include military law. Adjutants collect data on troops, battles, and conditions. They then feed the information to commanders, who use it to direct troops.

Inspecting to Succeed

Passing inspection is an important moment in the life of any soldier. As contributors to the larger body of a platoon, company, or regiment, soldiers undergo regular inspections to sustain order in an army. The term “well-regulated militia” was an early concept in the United States and one with which George Washington struggled daily during our fight for independence.

On October 29, 1777, the first Inspector General was appointed to help transform the Continental Army into a fighting machine. Inspector Generals were charged with oversight of training, reviewing troops, establishing discipline, and upholding justice within the command structure. Baron Frederick William Augustus Von Steuben served as America's first Inspector General of note. By 1778, Lt. Gen. Von Steuben, who spoke no English, created an office for the role and began to mold the Continental Army into an effective force. From that point on, the U.S. Army maintained—and continues to maintain—an Office of the Inspector General to oversee duties ensuring the fighting trim of soldiers.

A Confederate Army Emerges

The roles of the Adjutant and Inspector Generals are typically two separate commands. However, President Davis selected Samuel Cooper for a combined role in 1861. The need to mobilize quickly and Davis’s habit of favoring personal relationships over talent—he knew Cooper well and they both served as Secretary of War during the 1850s—led to Cooper’s appointment to the hybrid position. A New York native, Cooper also served in the U.S. Army’s Adjutant General Office starting in the late 1830s. His service in the Second Seminole War (1841-1842) and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) prepared him for the monumental role in establishing a Confederate army.

Cooper was the first general officer in the Confederacy. Many may recognize the names of Lee, Johnston, and Beauregard, but Gen. Cooper—as the longest-serving Confederate military officer throughout the war—was technically senior to them all. As Lee and his fellow field commanders assembled armies from local militias, Cooper developed an administrative and organizational blueprint for the CSA. His headquarters were located in the War Department building (formerly the Richmond Mechanic’s Institute), just southwest of the Capitol Grounds where the modern 8th and Main building now stands.

The Uniform and Dress of the Army of the Confederate States, published in 1861, was a valiant attempt at standardizing the Confederate fighting attire. Not surprisingly, it followed basic tenets of the U.S. Army, such as the colors for piping or facings for artillery, cavalry, infantry, and medical departments. The manual designated “cadet gray” as the color of the Confederate uniform, which often changed in style according to geography as well as during different phases of the war. The Adjutant and Inspector General could prescribe a cut and color for the uniform, but the South's manufacturing capacity proved insufficient in creating consistency in material.

When not engaged in updating manuals or drafting general orders, the Adjutant and Inspector General was swamped in field reports. As chief administrator of the armies, Cooper oversaw a central node for information. Field reports included a basic synopsis of a skirmish or battle, a list of wounded/killed/missing, and any weapons seized. Cooper also received intelligence reports.

In August of 1862, reports kept Cooper apprised of a flotilla on the James. The Seven Days Battles had ended Union General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, and, after fierce fighting, both sides were prickly as to the next move. Two gravely wounded armies had shed nearly 40,000 souls within earshot of Richmond. Cooper kept the butcher’s bill while retaining an ear to the ground for attack.

Behind the pomp and circumstance of dashing sabers, sparkling bullion, and cockaded slouch hats stood the Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office. This was where the true cost of war was measured in cold, calculating figures; where partisan rangers in the hinterlands were kept in check to maintain order. From this corner, Cooper and his men attempted to hold together an army partially ruled by 13 governors. To be in the Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office meant having your finger on the pulse of the war.

Meanwhile, a seal sat on Cooper’s desk. A little more than an inch wide, it had been repeatedly pressed into sealing wax on letters to be dispatched to the field or to the Confederate government bringing updates from the frontlines.

Recognizing the Moment

How did an impression of this seal come to be in the copper box?

Capt. John F. Mayer served in a clerical role in the Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office in Richmond during the Civil War. According to William Butts, a philographer and contributor to Autograph magazine, Mayer collected signatures and surplus documents from his office. At some point, he took it upon himself to make a wax seal on cardstock using the brass seal of the office. According to collections records from the American Civil War Museum, Mayer may have evacuated from Richmond to Charlotte, N.C., in April 1865 with the records of the Adjutant and Inspector General's Office. He also saved a flag that had been used as the headquarters ensign of Robert E. Lee.

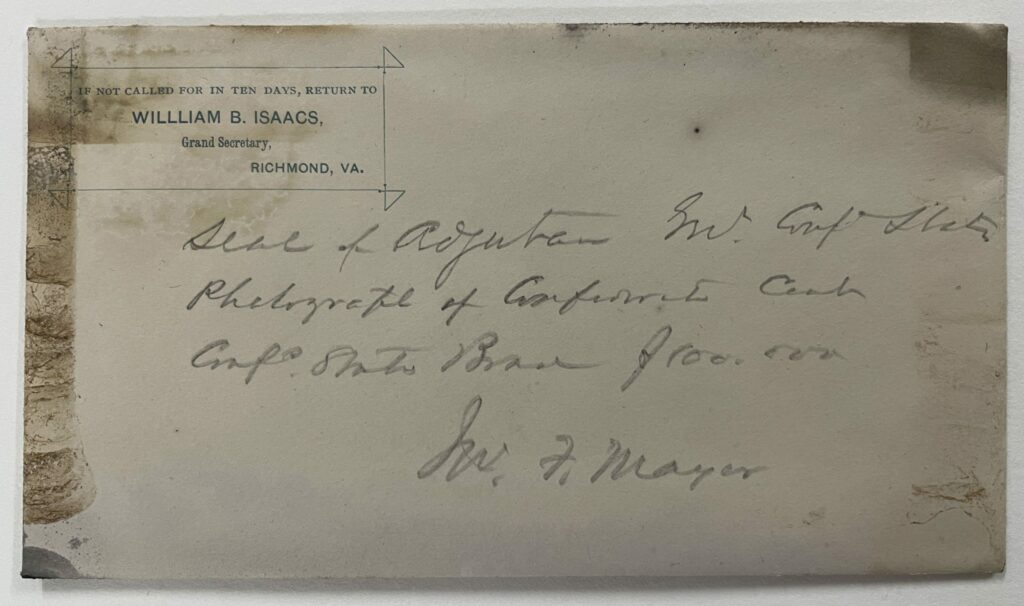

We can assume that Mayer worked closely with office records and had a penchant for saving iconographic items associated with the Confederacy. Mayer donated the seal and a registered $100,000 bond to William Isaacs, a Richmond-based Freemason who oversaw the collection of items for the Lee monument capsule.

As for Cooper, his role in the Civil War may be summed up as the chief curator of Confederate Army records. At the end of the war, fire ravaged building after building as Richmond set itself ablaze. The U.S. Army burned records in countless courthouses. Years later, when historians assembled the 127th volume of War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (commonly called the “Official Record”), much of the documentation used came from the pile saved by Cooper and the officers who worked with him in the Adjutant and Inspector General's Office.

Exploring the Symbol

The small wax seal was made by pouring molten sealing wax onto a piece of cardstock and then impressing the seal itself into the viscous wax. The sealing wax impression reflects a set of crossed cannons topped by what appears to be seven stars. The text “ADJT. & INSP.GEN.OFFICE.CSA” wraps around a ring surrounding the motif. A dotted border forms the outer bounds of the sealing wax. The material, which may have been altered by the conditions in the copper box, appears somewhat pink in color. Contrary to popular culture, not all sealing waxes were red. In fact, red was often used in personal or business correspondence during the 19th century to signify bad or urgent news.

The author has not viewed the actual seal. The seal was likely made from a brass or copper-alloy blank and may still exist. An engraver would have carved the design in reverse into the face of the seal, which weighed heavily enough to absorb heat and cool the wax.

Interestingly, the impression on the wax lacks clarity. Many wax seals, if kept clean, offer a perfect impression of their surface. Perhaps the wax was of poor quality. Or, the wax may have been diluted with lesser materials to provide for prolonged use during the war. If this wax seal was made during the Civil War, that may explain the poor quality of its impression.

This fall, DHR worked with the historic seal of New Kent County. William Wagner of York, Pa., engraved the seal, a solid brass disk, sometime during the mid-19th century. Wagner was a popular engraver and made several hundred seals for counties, courts, and companies. Edward Brown, a U.S. soldier, took the seal from the New Kent Courthouse grounds in June 1862. In October 2021, Brown’s great-great-grandson returned the seal to New Kent. DHR was approached during this time to inspect the seal and assess its condition.

At the moment, the location of the original seal from the Confederate Adjutant and Inspector General's Office is not known. However, Capt. Mayer saved its small wax representation for future generations. It is a testament to the hidden role of the office, which nearly concealed the identity of the highest-ranking Confederate general officer from our common knowledge.

—Brendan Burke

Underwater Archaeologist

Division of State Archaeology

•••

Sources:

Mayer’s collection of signatures

Mayer’s involvement with evacuated records