Ask an Archaeologist: Investigating a “corduroy" road

In July, I was asked to field visit what was described as a possible “corduroy road” in Sussex County just south of Wakefield. The potential for finding a real, intact historic corduroy road was minimal, as most would not have survived for long due to poor preservation conditions or because they were often destroyed by subsequent road improvements.

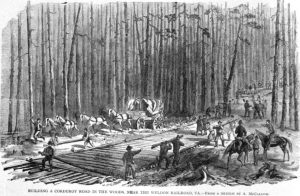

Corduroy roads are a series of logs laid parallel across a roadbed to allow passage of wagons, horses, or foot traffic through usually muddy or wet areas to prevent them from getting bogged down. It is an old technology that the military primarily utilized here in Virginia as an expedient means to improve rudimentary roads during the 19th century and possibly even the 18th century. It is likely that this method was used during the early colonial years of Virginia settlement when roads were quite primitive. The logs, when laid down in a linear pattern, resemble corduroy fabric, hence the name. These are different from "plank roads" constructed, as the name implies, of flat boards—historically a more common method of road construction throughout Virginia.

Archaeologists and historians have recorded only a few corduroy roads in Virginia and those were most often related to Civil War troop movements through muddy and nearly impassable areas. Those roads were discovered below current paved roads during improvements in recent decades. The examples seen to date have been significant but only partially intact due to less than perfect preservation conditions.

The one I inspected is near Wakefield, on the border of Southampton and Sussex counties, near Airfield Pond. After a muddy walk through swamps and standing water, we came to a slightly raised dirt roadbed about 10-feet wide or so. The roadbed was elevated no more than 10-to-12 inches but of sufficient height to stay dry, and it led to a series of logs laid down through the swampy ground. Stretching about 100 feet, in nearly perfect condition, the road was clearly visible and ran in a northwest to southeast path.

The logs making up the road each measure about 10-to-11 feet in length and about 5-to-6 inches in diameter. A few slightly larger in diameter logs were also visible and these had been flattened on top using an adze or axe. Both ends of most of the logs still had visible axe marks from the felling of the trees. A few had been chopped on one end and sawn on the other, indicating a log that was too long for the width of the road and that possibly two halves of the log’s length were used. The road continued to a point where it crossed a small streambed. Within the stream are still visible the remnants of what appears to be a support structure made of logs sticking vertically up out of the bed. Once the road crossed the stream, the ground was slightly higher and no remnants of logs were visible but the ground had been formed into a raised roadbed for another 40 feet or so onto even higher ground.

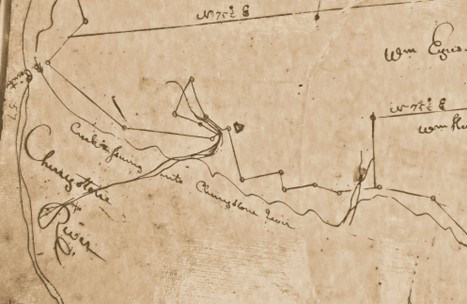

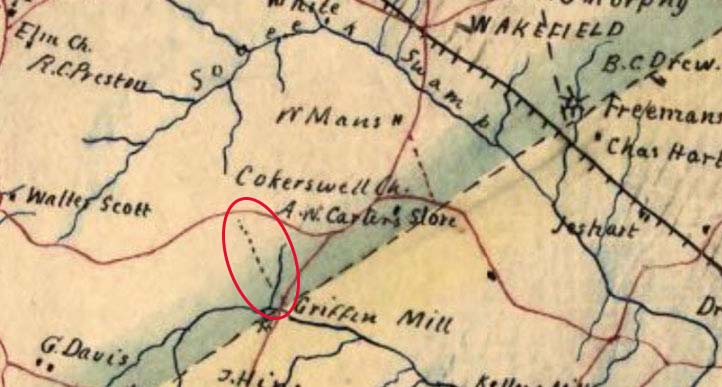

It is uncertain when this road was constructed but it appears on Civil War–era maps and continues to appear on maps into the early 20th century. It seems quite possible that its origins may relate not to the military but to Griffin’s Mill, which once operated in this area and to which the road appears to lead.

Further research is ongoing into the mill. No archaeological investigations have been conducted there and the records are incomplete. Reportedly, the mill was in operation as early as the late-18th century. Could it be that the miller or local farmers constructed the road to allow them easier transport of their goods to the mill?

More work is planned to study the road, including taking a small sample of a few of the logs for analysis to determine the type of wood. It may be cypress, which would help explain its excellent preservation. The fact that the wood has been in wet ground and underwater for so long has likely also helped preserve it. Detailed mapping and recording efforts will take place later in the fall (when the cottonmouths have retreated for the season). Stay tuned.

If you have any knowledge of the history of Griffin’s Mill or the general area, DHR would love to hear from you. Please send me an email if you have such information.

–Mike Clem

Archaeologist, Eastern Region Preservation Office, DHR