Cornerstone Contributions: Buttoning on a Navy in Haste

A small, brass lapel pin made from a button was found in the cornerstone box from the Lee Monument. It comes from a Confederate naval officer’s uniform and bears the seal of the Confederate States Navy. When we think of the Civil War, the navies of both sides are frequently forgotten, but the Civil War at sea was an important part of the struggle. Blue and gray sailors fought on the high seas as well as in muddy rivers to control territory and keep vital supply lines open. This little button highlights the importance of naval conflict during the Civil War.

Richmond and the Confederates States Navy

The Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America established a navy on February 21, 1861 and appointed Stephen Mallory as Secretary of the Navy. Formerly the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs for the United States, Mallory arrived in Richmond in June of 1861 and began assembling his navy for war (Coski 1996:1-2). The state of Virginia also recognized a need for naval defenses and organized the Virginia State Navy, which ended up as a squadron within the Confederate States Navy.

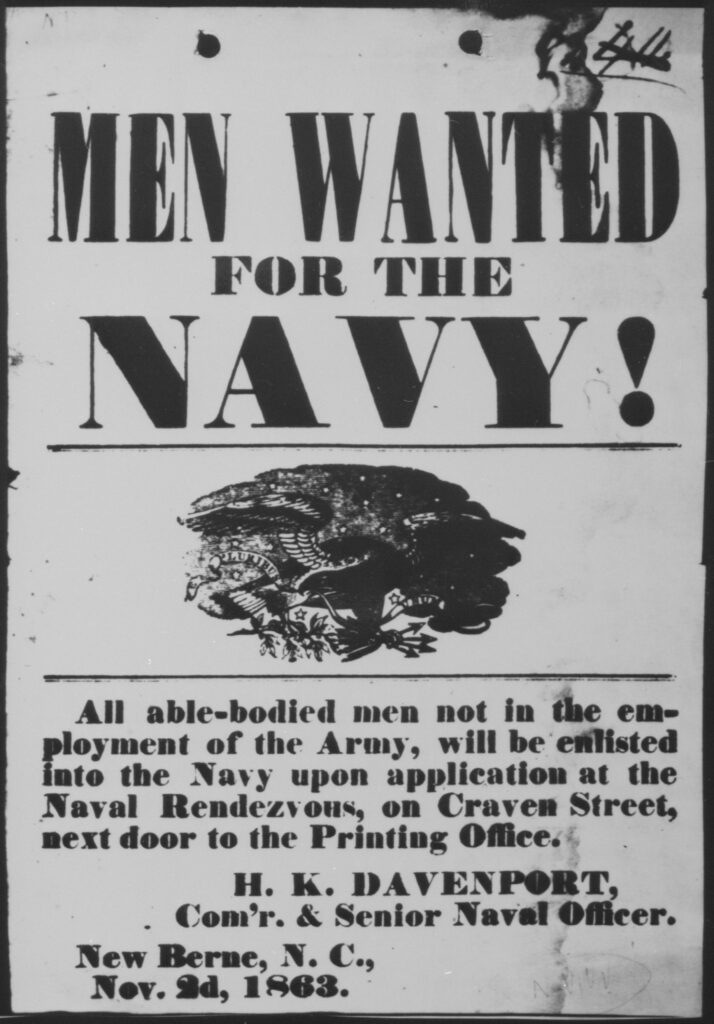

Building a navy is no small task for any country. As many governments have discovered, the money required to maintain a fleet of ships can be astounding. No matter how expensive, Confederate ports required protection and sea-lanes for outbound cotton and inbound war supplies were crucial to keep the economy running. The U.S. Navy, under the direction of the War Department, enacted a total blockade on the Confederacy early in the conflict. Warships stationed around southern states bottled up ports and choked trade.

Located at the upper reaches of the tidal James River, and only one hundred miles from Washington, D.C., the Confederate capital at Richmond was vulnerable to attack from both land and water. Seagoing vessels could sail to within cannon-shot of downtown. At the beginning of the war, Confederate defenses of the lower Chesapeake Bay and the James River were centered around the port of Norfolk (Coski 1996:1-2; Dabney 1996:300-303). However, Confederate Norfolk was abandoned in May of 1862 and the gray fleet withdrew up the James River. The focus of the U.S. Navy was now on Richmond.

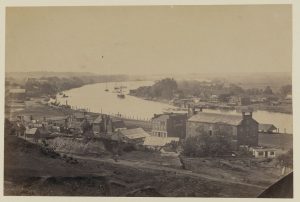

Confederate naval forces below Richmond became the James River Squadron. From tugboats to repurposed civilian vessels, the little navy boasted an academy and was led by the flagship CSS Patrick Henry. Rocketts, then a suburb of Richmond, was situated on low-lying ground by the river and hosted a long wharf for seagoing ships. Early in the war, the need to build Confederate naval vessels gave rise to a naval yard in at Rocketts. The Battle of Hampton Roads, fought in March of 1862, proved the effectiveness of ironclad ships and so shipbuilding facilities at Rocketts began to produce ironclads such as the CSS Richmond, CSS Fredericksburg, and CSS Virginia II.

Founding a Floating Force – Tredegar Iron Works

In 1861, Richmond was the third largest city in the Confederacy and a significant southern industrial center with five railroad lines, considerable hydropower, iron manufacturing, milling, and port capacity to handle trade. Tredegar Iron Works was a major manufacturer of iron goods and a primary factor in the decision to choose Richmond as a capital for the Confederacy. Located on the northern bank of the James River, Tredegar supplied projectiles, locomotives, railroad rail, ordnance, and iron plating used to armor ironclad warships, all while continuing to manufacture civilian wrought and cast-iron goods. It was Tredegar’s ability to produce ordnance and armor that enabled Richmond to assemble the James River Squadron.

Steel Gray for an Iron Navy

As we discussed with the formation of the Confederate Inspector and Adjutant General’s Office (https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/news/corner-stone-contributions-the-seal-of-the-office-of-the-adjutant-and-inspector-generals-office-csa/), the newly formed government and military often mirrored the government from which they sought to secede. The Confederate States Navy was no different. Early changes to uniform the service and change the color of the uniform from blue to gray aroused grumbling from tradition-bound sailors who only knew blue as the color of the sea uniform. Besides, a vast store of blue uniforms captured from Gosport were at hand. Nonetheless, the Confederate naval uniform was designated as steel gray but were otherwise indistinguishable from the cut of the U.S. Navy.

A Confederate States Navy vest or cuff button was placed within the contents of the Lee Memorial cornerstone box. The button appears to be

tarnished from years of use and the backside of the button was modified so that it could be worn as a lapel pin. The front of the button depicts the seal of the Confederate States Navy. “CSN” is embossed below a fouled anchor overlaying crossed cannons. The reverse side of the button contains a maker’s mark that reads, “Smith and Sons Piccadilly”.

The button is attributed to Captain Dennis Bremond. Capt. Bremond was an acting master (captain) in the Confederates States Navy aboard C.S.S. Florida in 1861. Although records indicate he was discharged from service in 1862, Bremond appears to have served aboard C.S.S. Louisiana early in the year and later on at Richmond and Charleston. In Charleston, Bremond was appointed as master of C.S.S. Huntress in January of 1863.

C.S.S. Huntress (Tropic)

According to the Naval History and Heritage Command (2022), Huntress was built as a mail packet at New York City in 1838. The vessel was painted black and was described as having a narrow beam, large side-wheels, and a low profile. Each of these traits allowed the vessel to be stealthy, hard to catch, and hard to outrun. The State of Georgia acquired Huntress in March of 1861 and eventually transferred to the Confederate States Navy. The vessel mounted three guns and was the first vessel to raise the Confederate flag at sea. Huntress was eventually sold to A. J. White & Son, a Charleston merchant, where it was converted into a blockade runner and renamed Tropic. The vessel met an untimely fate on January 18, 1863 when it accidently caught fire as it attempted to escape Charleston during an attack while transporting turpentine and cotton. Crew, including Captain Bremond, were rescued from the wreck by U.S.S. Quaker Hill and sent to New York as prisoners of war. For Bremond, this was the end of his Civil War (Harrington et al 2022; Naval History and Heritage Command 2022).

From Europe to Confederacy and from Cuff to Lapel

This little button, a relatively rare relic of the Civil War, was witness to a unique sector of the war, the war at sea. Conflict on the high seas was a struggle to contain and strangle the Confederacy for the U.S. Navy. For the rebel forces, it was a fight for survival. The Confederate Navy never ascended to a unified fighting force, despite significant effort and funds spent. It was instead, a splintered series of commands each operating in a micro-theater such as a harbor, a river, or foreign mission. Predation upon the merchant shipping of the United States was more effectively handled under letter of marque by privateers.

The maker’s mark on the back of the button tells us that it came into the Confederacy aboard a blockade runner from England, perhaps via Bermuda or the Bahamas. Its trip to the Confederacy was likely an amazing and dashing adventure by itself. This also speaks to foreign involvement with the Confederacy. Later, during the 19th century, when the U.S. Navy became a dominant global force, British naval officers may have regretted not supporting the Confederacy more as a way to break up the United States and prevent its navy from ultimately becoming a dominant global force.

Perhaps some of the tarnish on the button came from the fire and sinking of Tropic? No doubt, a reflection of flames would have been seen on the gilded face of the button as Capt. Bremond fought to save his ship. After the war, the button’s loop was removed and a pin soldered on the back to be worn on a lapel. Its new use was a symbol of a largely unknown Confederate States Navy and reflected a different flame, the Lost Cause. After at least one transatlantic crossing, combat at sea, and the loss of a command, the button was finally, to use a nautical term, ‘moored’ in the base of the Lee Monument as a contribution from the Civil War at sea.

- Patrick Boyle, Assistant Underwater Archaeologist

Brendan Burke, Underwater Archaeologist

Virginia Department of Historic Resources

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

References

Dabney, Virginius

1996 Virginia: The New Dominion, A History from 1607 to the Present. University Press of Virginia. Charlottesville.

Coski, John M.

1996 Capital Navy: The Men, Ships and Operations of the James River Squadron. Savas Woodbury Publishers. Campbell, CA.

Harrington, Sion, Terry Foenander, and Bruce Long

2022 NC Civil War Sailors Project. http://rblong.net/sailor/br.html

Lord, Francis A.

2014 Civil War Collector's Encyclopedia: Arms, Uniforms and Equipment of the Union and Confederacy. Dover Publication. Mineola, NY.

Naval History and Heritage Command

2022 Huntress. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/confederate_ships/huntress.html

Porter, David Dixon

1886 The Naval History of the Civil War. Sherman Publishing Company, New York, NY.

Russell, A. J.

1864 Photograph. View of Rocketts & James River. Richmond, James River, VA. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2005684435/

Symonds, Craig L.

2012 The Civil War at Sea. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

National Register of Historic Places

2012 "Tredegar Iron Works National Historic Landmark nomination". Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, VA.