Cornerstone Contributions: Calling Cards—An Introduction From the Past

DHR State Archaeologist Elizabeth Moore examines the three types of calling cards found within Richmond’s Lee monument cornerstone. The cards provide a glimpse of the competing viewpoints that prevailed in the decades following the end of the Civil War.

DHR State Archaeologist Elizabeth Moore examines the three types of calling cards found within Richmond’s Lee monument cornerstone. The cards provide a glimpse of the competing viewpoints that prevailed in the decades following the end of the Civil War.

Social Calling Cards

In the era before telephones and social media, calling cards provided a way for individuals to initiate visits, convey messages, and announce one’s arrival at a social event. First used in 15th-century China, paper calling cards became popular in France, then in London in the 17th century.1 By the 19th century, they had become an essential component of social etiquette in Europe and the Americas. Calling cards served both utilitarian purposes and as status symbols. Calling cards were a way to schedule social visits to share information and organize events, but they also allowed selected individuals entry to social circles while keeping others at a distance.

Victorian etiquette surrounding calling cards among the social elite was complex and included many rules, which, if violated, could mean social self-destruction. In typical use, a visitor would deliver a calling card to a home—sometimes in person, other times through a servant—to announce one’s arrival or to request a visit. If the recipient wasn’t home or didn’t wish to meet, a servant would accept the calling card, or the card would be left on a silver tray in the entrance hall. Even when a visit was permitted, a calling card would be left on the tray as evidence of the meeting. A tray filled with calling cards indicated one’s social desirability. Cards from visitors with the highest social status would be left on the top of the stack for others to see. When accepted, visits were formalized and had a strict set of rules. Visits only took place in the late morning or early afternoon, and typically consisted of twenty minutes of polite conversation.

Messages could be written on the backs of calling cards or conveyed through code. Women’s cards were approximately 2.75 high to 3.5 inches wide. This meant that messages were, by necessity, short. Men’s cards were slightly narrower, so they could fit in a breast pocket.2 Messages conveyed times for a visit, regrets or condolences, or the purpose of a visit.

In the mid-19th century, an individual could encode messages by turning the corner of a card. A visit in-person was indicated by turning the right-hand upper corner; a congratulatory visit by turning the left-hand upper corner; a condolence visit the left-hand lower corner; and turning the right-hand lower corner meant the person was leaving on a long trip. Gentleman callers would initial their cards with an abbreviation for a French phrase—p.f. for congratulations (pour féliciter), p.c. for condolences (pour condoléance), p.p. for an introduction (pour présenter)—to convey their message.

Calling cards, which were at first simple rectangles printed with names, began to display embellishment, color, and expensive printing techniques during the Victorian era. Cards featured scalloped borders, fancy shapes, embossing, lithography, attached photos, and even hand sewn borders, among other decorations.

Masonic Emblem and Exchange Cards

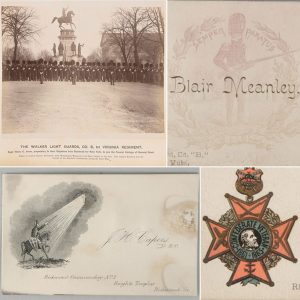

The cards found in the cornerstone box served a different function than the more widely used social calling cards. The cards from J.H. Capers and Edward W. Price are Masonic cards. They indicate the cardholder’s affiliation with the Freemasons or Knights Templar. Similar in form to calling cards, printers referred to these cards as emblem or exchange cards. Unlike social calling cards, emblem cards were usually exchanged in-person between Freemasons. Emblem cards were collected at the conclaves of Freemasons and Knights Templar. They functioned as souvenirs of the event.3

The upper left corner of Price’s card contains a Knights Templar seal, which is an emblem of a cross-in-crown on top of a Maltese cross with crossed swords behind it. The seal alludes to the cross of Christ. Encircling the cross-in-crown is a motto in Latin, In Hoc Signo Vinces: “in this you will conquer,” or “in this sign we will conquer.” The same motto appears on Capers’s card, but it is placed above a cross in the sky shining light down upon a Knight Templar on horseback, who raises his sword to the cross.

The inclusion of these cards in the cornerstone box is one more indication of the Freemasons’ and Knights Templar’s role in the establishment of Richmond’s Lee monument, as well as the pride that Freemasons took in being involved with this project.

Veteran's Cards

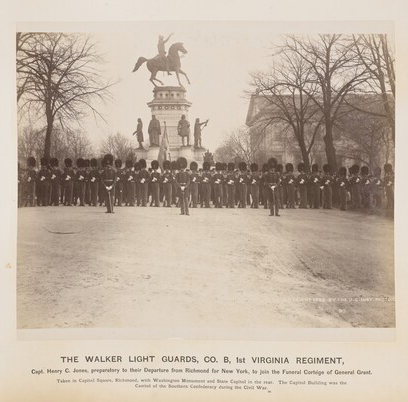

The cards from Blair Meanley and P. J. White are veteran’s cards that identify their service units. Meanley and White were veterans of the Confederacy, and, like most veterans, their service was a life-defining period. Presenting a card that announced their service was a point of pride—it publicly declared the individual’s political alliance during the war; it provided a means of group identification when meeting strangers; and it helped form social alliances with those of similar affiliation.

Meanley’s card contains the image of a soldier surrounded by a laurel wreath with the words Semper Paratus, “Always Ready.”

White’s card exhibits an emblem with multiple components that identify his alliance with the Confederacy, including the words “Confederate Veteran 1861-1865,” an engraved image of General Robert E. Lee within a Maltese cross with symbols of the armed forces, and a plaque with “CSA” (Confederate State of America). White’s card also featured the second national flag of the Confederate States of America. Also known as “The Stainless Banner” or the “Jackson Flag,” it had draped the coffin of Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Adopted in 1863, this design was supported in a series of editorials by William Tappan Thompson, editor of the Savannah Morning News. By placing the Confederate battle flag on a white field, Thompson argued that “the White Man’s Flag” should represent the Confederacy. “As a people, we are fighting to maintain the heaven ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race: a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause.”5 That P.J. White chose this flag and associated symbols to be printed on his card and included in this monument sends a deliberate and distinct message of his position on emancipation and efforts toward racial equality.

The cards for Meanley and White present opposing ideologies after the war. Meanley belonged to the Walker Light Guards, who participated in the seven mile funeral cortège for President Ulysses S. Grant, Commanding General of the United State Army. White’s card displays a flag designed to support white supremacy.

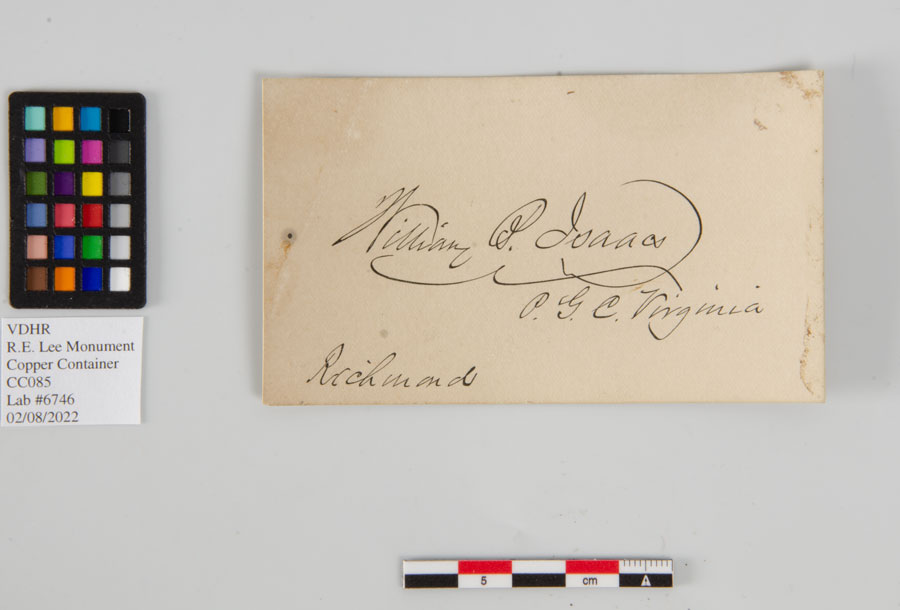

An Inadvertent Card

The last card presented here has handwritten information on both sides. The name H.L. Turner is printed on one side and William B. Isaacs on the other. Unlike the other cards seen here, these names were not printed in advance. The presence of both names on the same piece of paper suggests that their inclusion may not have been planned, but may have been opportunistic. The Richmond Dispatch inventory of the cornerstone box did not include a card with Turner’s name. Isaacs’s card was submitted by W.H. Sands, who also contributed a “programme Ancient Order Nobles of Mystic Shrine laying corner-stone of Lee Monument.” William B. Isaacs, also a Freemason, was responsible for the collection of items for the cornerstone box. According to The Richmond Dispatch inventory, Isaacs provided other items for the box that included “copies of charters issued by Grand Lodge, Grand Chapter and Grand Commandery of Virginia to its subordinates,” a “Richmond Directory,” and “an assortment of United States silver and copper coins.” Isaacs’s information is neatly written in straight lines on the card. Although the handwriting is similar, the information for H.L. Turner was written in more of a hurry—the letters are not as neat or embellished, and the lines of text are not straight and laid out as we see with that of Isaacs.

These cards provide brief yet telling pieces of information about the men represented. The men’s pride in their fraternal organizations, their military service, and their positions on the results of the war are told in the text and symbols they chose to include. The cards, like the other objects found in this box, represent the opposing viewpoints of the Lost Cause narrative and post-war reconciliation, viewpoints that continue today.

—Elizabeth Moore

DHR State Archaeologist

State Archaeology Division

•••

References Cited

1. Banfield, Edwin. Visiting Cards and Cases. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Baros, 1989

2. "Calling Cards and Visiting Cards: A Brief History," by Claire Green, September 12, 2016. https://hobancards.com/blogs/thoughts-and-curiosities/calling-cards-and-visiting-cards-brief-history. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.

3. "Masonic Emblem Cards: Victorian Tradition in a Fraternal World," March 3, 2015. https://nationalheritagemuseum.typepad.com/library_and_archives/2015/03/masonic-emblem-cards-victorian-tradition-in-a-fraternal-world.html. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.

4. Grand Chapter Royal Arch Masons in Virginia

2022 https://virginiaroyalarch.org/chapters/. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.

5. Preble, George Henry (1872). Our Flag: Origin and Progress of the Flag of the United States of America. Albany, New York: Joel Munsell. pp. 416–418. OCLC 423588342.

6. "Confederate Virginia Troops, 5th Regiment, Virginia Cavalry." National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=CVA0005RC01. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.

7. Driver, Robert J., Jr. 5th Virginia Cavalry. H. E. Howard, Inc. Lynchburg, Virginia.

8. "First Battalion Virginia Artillery," Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 17. Reverend J. William Jones, Ed. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0274%3Achapter%3D1.14%3Asection%3Dc.1.14.265. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.

9. "Norfolk Masonic Temple Atlantic Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M." http://www.norfolkmasonictemple.com/atlantic-lodge-no.-2.html. Accessed Feb 15, 2022.