Cornerstone Contributions: Paying for Rebellion: Confederate Currency in the Lee Cornerstone Box

Prior to the Civil War, the U.S. Department of Treasury held the sole authority to issue currency for the United States. Individual states were prohibited from minting coinage and establishing bills of credit. However, private institutions, such as banks, municipalities, and insurance companies, were allowed to issue scrip, or substitutes, for legal currency. For example, banks could issue certificates payable on demand. This was fairly risky for the bearer because if the bank defaulted, then the certificate would be worthless.

In the 19th century, it was better to use authentic currency to obtain necessities. Using legal currency or scrip was not the only way to pay for items in the years leading up to the Civil War. If you were living in 1850 and wanted to make a purchase, you might pay in small amounts of gold and silver, or even use your own merchandise to trade (Sumner 1874:60-65; UOCL 2022).

The Switch to Paper

Although the government at the time had the ability to print paper currency for almost 80 years, the United States did not issue paper notes until well into the Civil War in 1862. The Legal Tender Note was created in direct response to the outbreak of the war. The government realized there would be a higher demand for metals and did not want to waste the supply on coinage.

A fiat currency, the Legal Tender Note was not backed by gold, silver, or any specific commodity. Even so, it was considered the official currency of the United States. The switch to a paper currency allowed people to carry more money without being weighed down by coins. This was a noticeable change for the everyday lives of citizens, who were used to paying in coinage, and is comparable to the modern-day transition from physical to digital currency (Slabaugh 2000; UOCL 2022).

Confederate Currency

The South also printed paper currency. In fact, it was the only type of currency issued within the Confederate States during the Civil War. Confederate paper money could be converted into bonds, but it was not payable to the bearer on demand. Although the CSA initially considered using coinage, the primary mints of the South were taken by Union forces early in the war. Paper money was therefore chosen as the main currency (Slabaugh 2000; Fricke 2012:5-7).

Seven Southern states formed the CSA on February 8, 1861. To organize, the states created bonds to raise money for the new government. Establishing a unique legal currency was a way to legitimize the fledgling Confederate government. However, unlike in the Northern states, the printing of currency in Southern states was poorly regulated. Every Confederate state, along with many local governments, issued their own currency. This led to a severe lack of consistency in payment methods between states (Slabaugh 2000; UOCL 2022).

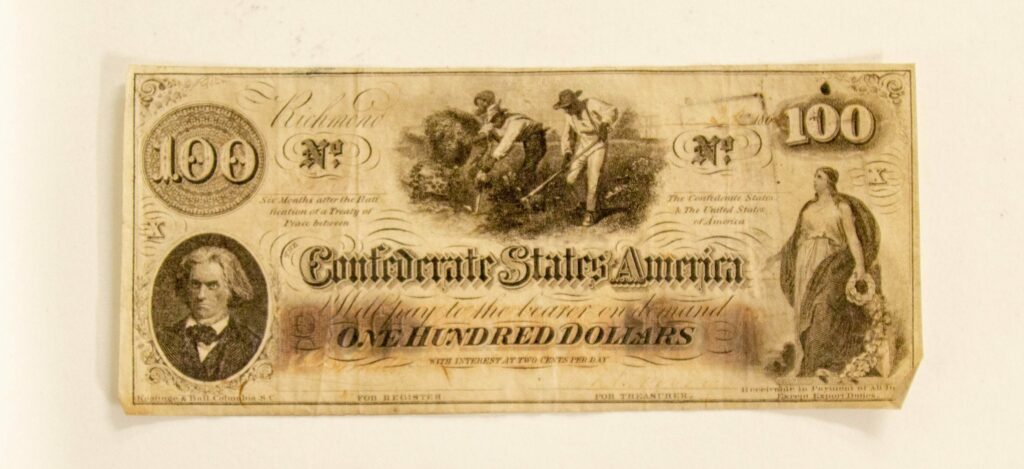

Confederate paper money was also considered a fiat currency with no gold or silver backing the notes. This meant that it was essentially a line of credit to the bearer of the notes. As seen on the $100 note, the bearer could be paid the value of the bill “six months after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the Confederates States & the United States of America.” As the war dragged on, the agreement changed from six months to two years (Fricke 2012:9; Slabaugh 2000).

Compared to Northern “Greenback” notes, Confederate money was known as “Greyback” or “Blueback” notes. Currency printed in the Confederate States featured artistic depictions of core values and CSA infrastructure. Imagery of ships, wagons, Greek gods, and enslaved laborers working in fields were commonly found on Confederate currency. These scenes were often accompanied by allegorical images symbolizing liberty and independence. Some notes, however, did not depict scenes glorifying the South. They would instead reuse images from currency issued before the Civil War (Fricke 2012:9; Slabaugh 2000).

Cornerstone Box Notes

F.W. Jones donated a variety of Confederate currency notes to the Lee Monument cornerstone box in 1887. The $100 bill was printed in Richmond in 1862. The note displays imagery of enslaved laborers tilling a field, with John C. Calhoun in the lower left and an allegorical female figure in the lower right. A faint stamp can be seen on the right side of the image. The bill is a T-41 note from the fourth series of Confederate currency. There were seven series of bills in total printed for the CSA (Fricke 2014).

DHR conservation intern Hannah Sanner tested the Confederate notes found within the cornerstone box and discovered that all of the bills were printed using iron gall ink. Conservators also noticed red coloring on a few of the bills. The pigment on the $100 bill consisted of lead, while the tints on the $0.50 and $5 bills were mercury-based.

Here, a list of all the Confederate bills found inside the cornerstone box:

$0.50 note featuring Jefferson Davis. T-63 from the sixth series. Archer & Daly. Richmond, VA. (1863).

$1 note featuring Clement Claiborne Clay. T-55 from the fifth series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (1863).

$1 note from the Bank of the Commonwealth. Richmond, VA (May 1, 1861).

$1 note from the Monticello Bank. Charlottesville, VA (May 1, 1861).

$1 note from the Real Estate Banking Company. Selma, AL (Unknown Date).

$2 note featuring Judah P. Benjamin. T-61 from the sixth series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (February 17, 1864).

$2 note from the Monticello Bank featuring a three-masted sailing vessel. Charlottesville, VA (1861).

$5 note featuring Virginia State Capitol. T-53 from the fifth series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (April 6, 1862).

$10 note featuring horses and a cannon. T-68 from the seventh series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (February 17, 1864).

$20 note featuring Tennessee Capitol. T-67 from the seventh series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (February 17, 1864).

$50 note featuring Jefferson Davis. T-66 from the seventh series. Keatinge & Ball. Columbia, SC (February 17, 1864).

$100 note featuring John C. Calhoun and enslaved laborers. T-41 from the fourth series. Keatinge & Ball. Richmond, VA (1862).

Problems with Confederate Currency

The first Confederate paper notes were printed in Montgomery, Ala., the preliminary capital of the Southern states. On May 24, 1861, the capital moved to Richmond following Virginia’s secession from the United States (Slabaugh 2000).

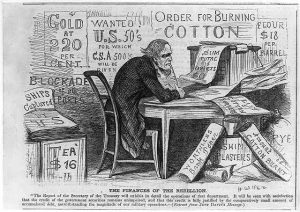

Notes printed in the Confederacy were very inconsistent. Multiple denominations used a variety of different designs. Due to the lack of uniformity in Confederate paper money, forgers could produce counterfeits easily and frequently (Fricke 2012:8). Forgers cut the notes by hand and signed them before releasing to the public. Clean edges on the paper indicated that a bill was counterfeit currency.

No noticeable signs exist to suggest that the Confederate currency from the Lee monument cornerstone box is fake. Famously, “souvenir” Confederate money produced in Northern states was so similar to the true currency that it would be mistakenly accepted in the South. Consequently, Union soldiers often carried souvenir money to use in Southern states. From 1861-1864, the Confederate government issued a total of 72 different types of currency (Fricke 2014).

Once distributed, Confederate currency immediately became susceptible to inflation. Unlike the United States, the Confederate government did not set a limit on the amount of paper money that could be printed. This caused rapid inflation. People expected the Civil War to be over quickly, but as it dragged on, they began to lose faith in the Confederacy, which only exacerbated inflation in the South.

The overall quality of Confederate currency declined throughout the war. The first notes were worth only 95 cents compared to the dollar in gold, and that value quickly fell. By 1863, the notes were worth 33 cents to the dollar. Two years later, they were worth less than 2 cents to the dollar. Southerners continued to use the currency for at least a month after the end of the war in 1865 (Slabaugh 2000). After that, the bills became worthless and could not be converted into anything else. Many Southerners lost their fortunes as a result of using Confederate currency throughout the war.

—Patrick Boyle

Assistant Underwater Archaeologist

Division of State Archaeology

•••

References

Fricke, Pierre

2012 - Confederate Currency. Bloomsbury Publishing, New York, NY.

2014 - Collecting Confederate Paper Money-Field Edition.

Green, Duff

1864 - Facts and Suggestions Relative to Finance and Currency Addressed to the President of the Confederate States. J.T. Paterson & Co. Augusta, GA.

Slabaugh, Arlie R.

2000 - Confederate States Paper Money: Civil War Currency from the South. Krause Publications, Iola, WI.

Sumner, William G.

1874 - A History of American Currency. Henry Holt & Company. New York, NY.

University of Chicago Library

2022 - Guide to the American Paper Currency Collection 1748-1899. Online. Accessed 26 January 2022].