Cornerstone Contributions: Where Are the Women?

White women served a critical role in the planning, fundraising, and design of the Lee monument yet none of the objects in the cornerstone box reflect their work. The only items related to women are a report of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (a group never involved in the Lee Monument) and several items women donated, all of which focused on veterans.

Among the myriad objects placed in the cornerstone box, it is curious that none reflects the central role Confederate women played in the Lee Monument’s creation. The only items related to women are a report of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (a group never involved in the Lee Monument) and several items women donated, all of which focused on veterans. Despite Confederate veterans’ near constant adulation of Confederate women at Memorial Day speeches and other occasions, perhaps the two-decade long battle they had endured with Richmond’s women over the monument had driven them to conveniently forget the critical role white women had served in the planning, fundraising, and design of the Lee Monument.

Following Robert E. Lee’s death in October 1870, a group of ex-Confederates met in Lexington, Virginia, forming the Lee Memorial Association, with the expressed purpose of erecting an equestrian statue on the Washington College grounds (where Lee had served as president until his death), a bust in the chapel, and a recumbent statue on his tomb.[1] But other Virginians, namely those in Richmond, believed Lee should be laid to rest in Hollywood Cemetery where so many of his men now reposed. Mary Custis Lee, the general's widow, temporarily put an end to disputes over his burial by agreeing to have him interred in a vault beneath the college chapel in Lexington. Disputes over a monument to the general, however, were only beginning.

The women of Richmond’s Hollywood Memorial Association (HMA) wasted no time in initiating their own organization to memorialize Lee. In 1866, the HMA along with other Ladies’ Memorial Associations (LMAs) had led the creation of Confederate cemeteries and established the practice of Memorial Day. Under the guise of mourning, women had been the key figures in these early Lost Cause ceremonies, and in the wake of Lee’s death, they claimed to be the guardians of Confederate memory. Rejecting the Lexington plan, the Ladies established a committee tasked with placing a bronze equestrian monument to the general in Hollywood Cemetery. In accord with their previous fundraising activities, they published a list of more than a hundred prominent Confederate leaders and soldiers, including nearly every member of the Lexington association, they wished would "act as assistants" to their committee. Notably present on the list of "assistants" was former Confederate general Jubal A. Early.

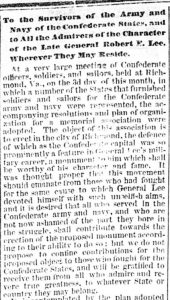

While women might be especially well-suited for organizing Memorial Days and honoring the common soldier, Early did not consider them fit to lead the most important Lost Cause task, that of honoring Lee. Instead, within a few weeks, he had established the Lee Monument Association (not to be confused with the Lexington-based Lee Memorial Association). In rhetoric no doubt aimed at the women of the HMA committee, Early believed that any effort to honor Lee should emanate from those who had fought under the general. "A sacred duty devolves upon those whom. . . he led so often in battle," Early claimed, although he had no intentions of confining the contributions to veterans alone, encouraging all those who "admire[d] and revere[d] true greatness" to donate. Early thoroughly resented any other effort to memorialize Lee, especially the Lee Memorial Association's efforts to enshrine Lexington as a memorial to Confederate leader and similar projects underway in New Orleans and Atlanta. Rather than encouraging white southerners to dot their landscapes with memorials to the famed general, Early insisted there be only "one grand Confederate Monument" situated in the heart of Richmond—one that was under his control.[2]

To gain a monopoly over the memorial movement to the late chieftain, by mid-November, Early had invited the HMA to "lend…their assistance" in collecting contributions. The women promptly agreed and formed auxiliary committees throughout the South—on the condition that they were to be considered equal partners in the endeavor. But Early and his associates had other plans. If the men could keep the women close enough, the women could not best the veterans' efforts to honor Lee. Early and the Lee Monument Association certainly knew how successful the HMA and other LMAs had been in raising funds for their cemeteries and other projects; their networks and money-generating capabilities must have been attractive to the men. The HMA women, however, were not nearly so naïve and passive as the men expected. Even though the women agreed with Early on several counts, including that the monument belonged in the former capital, they proved an especially troubling thorn in Early’s side, demanding full recognition and cooperation throughout the process. [3]

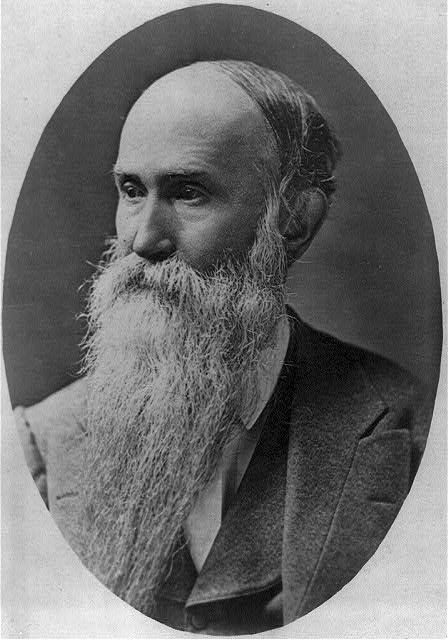

By 1871, a bitter and often cantankerous rivalry arose between the HMA (recasting its committee as the Ladies' Lee Monument Committee to be led by Sarah Randolph) and Early's Lee Monument Association, a rivalry enduring for nearly two decades[4]. Both competed to raise funding, with the veterans falling far short of the money flowing into the women’s coffers. Feeling bested by the women, Early embarked on a smear campaign, warning white southerners that some of the women’s agents were impostors and denying affiliation with the Ladies Committee.[5] For nearly fifteen years, the fires of hostility between Early and the women burned intensely as the agents for competing associations flooded towns and cities throughout the South trying to raise money for the Lee monument.

The divisiveness between Early's veterans and the women of the LLMC, combined with the confusion of multiple groups canvassing the region for contributions, managed to slow the Lee monument's progress to a near standstill within just a few years. In 1875, Governor James L. Kemper, a Confederate veteran, stepped forward to take the reins of the listless Lee memorial campaign. With Early's collaboration, Kemper commissioned a Board of Managers consisting of himself, ex-officers of the Confederate army, the state auditor of public accounts, and the state treasurer whose purpose would be the erection of a "Colossal Equestrian" statue of Lee on the Capitol Square. Early thus relinquished control of the movement and handed over his insufficient funds to the governor's board. There are some indications that the Ladies were approached to unite with the men, but it appears that the men never intended to give the women a position on the executive board. The women would not bequeath full control to the men. Not surprisingly, like the Early's Monument Association, the governor's group remained exclusively male.[6]

Despite the very public solicitations of the men's group, throughout the 1870s the LLMC continued its own fundraising ventures. But disputes over who might collect the most money proved to be only a skirmish in the male/female war over Lee's monument; the real battles unfolded over the statue's design. Early and the men preferred the selection of Edward Valentine, a Virginia sculptor who had crafted the recumbent Lee statue at Lexington. Sarah Randolph and the women, on the other hand, favored French artist Jean Antoine Mercié as they desired that the monument be construed as a masterpiece of art, reflecting the greatness of white southern culture. The women insisted, yet again, that they were the true and undisputed leaders of the memorial effort, and would submit to no man, including the governor. "Better no monument at all than an inferior one," Randolph quipped.

Even as Confederate veterans in New Orleans managed to complete and dedicate a memorial to Lee in 1884, the LLMC continued to forestall the Richmond project. Rejecting nearly every design model and refusing to relinquish their funds, the women spurned calls to cede their authority over the public representations of the Lost Cause.

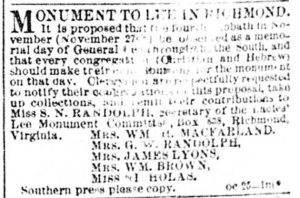

Finally, in 1886, former Confederate general-now-governor Fitzhugh Lee worked out a compromise association that included a new board of directors with representatives from the state government and LLMC, including Randolph and Elizabeth Nicholas. With fundraising nearing completion, the new association selected the women's sculptor of choice, Mercié. Early balked at the decision, describing Mercié's design as "General Lee on a 'bob tail horse,' looking like an English jockey" and implying that if it were erected, he would rouse "the survivors of the 2d Corps" to demolish the statue.[7] The women had prevailed, however, and the statue's cornerstone was laid amid a cold, drizzling rain on October 27, 1887.

Yet the women proved conspicuously absent from the cornerstone dedication.

In his remarks, Governor Lee mentioned the Hollywood Memorial Association’s (notably not the Ladies Lee Monument Committee’s) initial efforts to raise money in passing, but he lavished praise on Early’s association of veterans before introducing the general. Nineteenth-century southern, white gender norms precluded women from addressing the crowd, yet it is striking that the women had no objects included in the cornerstone. Of those women who donated objects (Mrs. H.O. Marshall, Nettie Lee Brown, Emma R. Ball, and Patti Leake), none appears to have had a direct connection to the LLMC or HMA. This is especially notable considering that some of the men who donated items, such as J.W. Randolph, were married to members of the Hollywood association. Likewise, one might have expected to find documents such as the Register of the Dead, Interred in Hollywood Cemetery published in 1869, which highlighted the women’s efforts to enshrine the Lost Cause in Confederate cemeteries. Finally, newspaper accounts suggest that although women attended the event, they did not participate in the procession to the cornerstone laying. In most monument Memorial Day and monument unveiling processions throughout the 1860s-1890s, LMA women rode in carriages at either the beginning or end of the line. In contrast, this event appears to have been exclusively a male affair, with 3,000 Confederate veterans marching in-step to the dedication site.

The LMAs and their successors the United Daughters of the Confederacy (est. 1894) proved largely responsible not only for the Confederate memorial landscape that flourished in first three decades of the twentieth century, but indeed the very success and longevity of the Lost Cause through their textbook campaigns, scholarships for Confederate descendants, and other efforts. Yet an examination of the objects found in the cornerstone would suggest women played little to no role in Richmond – indeed Virginia’s – most notable Lost Cause symbol. A recounting of the monument’s history, especially the contentious role of Confederate women in its establishment, serves as a reminder that silences often speak volumes.

- Dr. Caroline E. Janney

John L. Nau III, Professor in History of the American Civil War

Director, John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History

Other posts in the Cornerstone Contributions series may be found in DHR’s archive of Archaeology Blogs.

•••

For more about the role of the Ladies Memorial Associations in Richmond and Virginia, see Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause

Footnotes:

[1] Richmond Daily Dispatch , October 20, 1870; Gaines Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy , 51.)

[2] Jubal A. Early to Dabney H. Maury, December 14, 1870, item #50, Goodspeed's Catalogue 592 (Boston, Mass.: Goodspeed's Book Shop, n.d.), 11; "To the Survivors of the Army and Navy of the Confederate States and to all the admirers of the Character of the late General Robert E. Lee, wherever they may reside," November 1870, Lee Monument Association Records, Library of Virginia; Richmond Daily Dispatch , November 15, 1870; New York Times , October 28, 1870; Connelly, The Marble Man , 43-45.

[3] Richmond Daily Dispatch , November 15, 1870; Sarah N. Randolph to General Jubal A. Early, Richmond, March 13, 1871, Lee Monument Association Records, Library of Virginia.

[4] Richmond Daily Dispatch , November 15, 1870; Sarah N. Randolph to General Jubal A. Early, Richmond, March 13, 1871, Lee Monument Association Records, Library of Virginia.

[5] Richmond Daily Dispatch , November 15, 1870; Sarah N. Randolph to General Jubal A. Early, March 13, 1871, Lee Monument Association Records, Library of Virginia.

[6] Minutes of the Lee Monument Association, September 28, October 30, 1875, Lee Monument Association Records, Library of Virginia; "The Monument to General Robert E. Lee, Part 1," Southern , January – December 1889, APS Online, 187.

[7] "The Monument to General Robert E. Lee: History of the Movement for its Erection," Southern Historical Society Papers 17:185-205; Connelly, Marble Man, 45; Early quoted in Foster, Ghosts , 98-100; Savage, Standing Soldiers , 146-50.

Bibliography:

Connelly, Thomas L. The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American

Society. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence

of the New South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Savage, Kirk. Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in

Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997.