How did Virginians keep their spaces safe during the 1700s?

Whether they were made of functional iron or intricate brass, locks were the key to securing buildings and rooms in colonial-era Virginia.

By Laura Galke

During the 1700s, Virginia’s consumers were tempted by a greater variety of locks to secure their buildings and interior rooms. By the mid-1700s, the aesthetic appearance of locks became increasingly important. A lock’s style, quality and material conveyed to users an idea of what lay beyond the secured space and – importantly – who was authorized to access that space.

Unadorned, practical iron fixtures indicated that the space beyond was likely functional, private, and the domain of the property owners and their staff. Some locks were made from smooth, aggrandizing brass, or they boasted brass embellishments in their manufacture. Such hardware indicated that the space beyond, while private, was also special: a domain of refinement and perhaps for formal entertainment. Brass lock fixtures were a great deal more expensive than iron, costing twice as much.

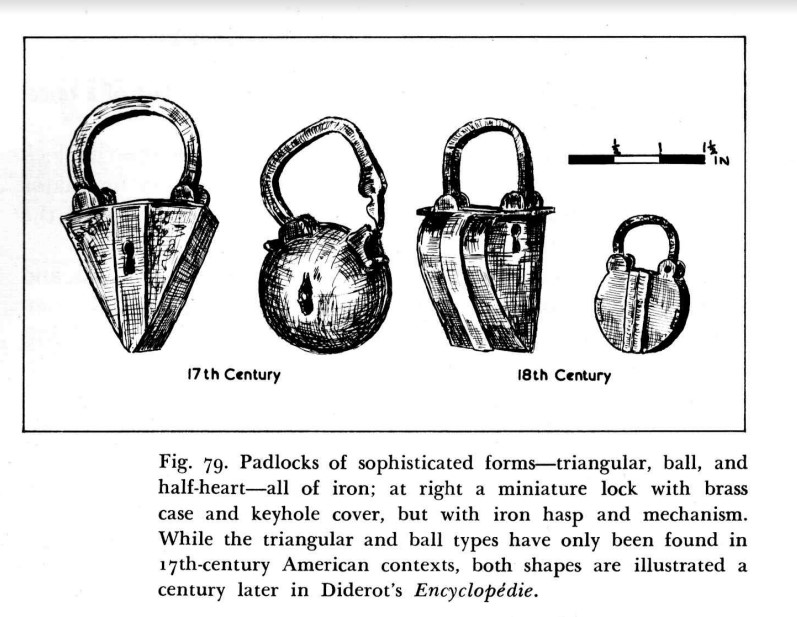

Padlocks, such as the pictured half-heart padlock (see Figures 1 and 2), provided portable security and were in common use during the 1700s. This style was used from around 1730 to 1820. This particular padlock was recovered by archaeologists in a colonial-era trash pit during the winter of 1983 in Gloucester County. It was carefully cleaned, conserved, and repaired by DHR conservation staff in 2003. The lock is currently featured in exhibits and has often been displayed for educational events.

The name of the half-heart padlock derives from its shape, as viewed from the side. The front of the lock features a curved surface that, when viewed from the side, resembles “half” of a heart shape. The half-heart style was popular among both French and English settlements in North America. The keyhole was located on the side of the lock, which compressed interior springs to release the entire curved shackle above. The large size of this particular half-heart is consistent with its use to secure a door as opposed to a small piece of furniture, such as a trunk. Padlocks were less expensive overall than doors that boasted built-in locking mechanisms. Iron padlocks were a functional and economical solution to securing space during the 18th century.

For further reading, check out the following below:

Chappell, Edward A.

2013 Hardware. In The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg, edited by Cary Carson and Carl R. Lounsbury. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. Pp. 259-283.

Hazzard, David K. and Martha W. McCartney

2004 Uncovering Old Gloucestertown: Archaeological Survey and Data Recovery at the College of William and Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, Virginia. Technical Report Series #6.

Noel Hume, Ivor

1969 A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Priess, Peter J.

2000 Historic Door Hardware. In Studies in Material Culture Research, edited by Karlis Karklins. The Society for Historical Archaeology, California, Pennsylvania, pp. 46-95.