Navigating the navigational works on the “Patowmack”

Author: Jillian Schuler

The roaring waters of Great Falls on the Potomac River attract thousands of visitors to Great Falls National Park each year. They were, however, detrimental to industry and agriculture in the region during the 18th-century, presenting the single largest impediment to transportation on the Potomac. Great Falls National Park features the history of the Patowmack River Company, also referred to as the Patowmack Canal Company, which strived to make the river navigable in the decades following the American Revolutionary War.

Evidence of the Patowmack Canal Company’s efforts remains, with one navigational structure located just south of the boat ramp in Riverbend County Park, directly adjacent to Great Falls National Park.

The team explored the sluice and the surrounding area to learn more about the archaeological, historical, and geographical context of the site. Materials such as bricks were identified near and around the site, as the DHR team, accompanied by the park director and archaeologists from the county park system, accessed the site via kayaks.

The wall of the sluice is constructed of long slabs of stone, overlapping like fish scales. As water passes over, especially strong flood currents, water pressure applies downward force to the wall, keeping it in place. Some of the stones are so naturally well-formed they were initially mistaken as milled timbers. The sluice builders likely sourced the stone locally, taking advantage of the accessibility, affordability, and quality of its natural formation. No appearance of tool marks, such as drill holes or dressing, were noted. The sluice has not been maintained for centuries now, however the wall remains largely intact highlighting the quality of its construction.

A sluice is a form of river infrastructure that deepens and fortifies a natural section of the river to make it more navigable. A sluice is like a skirting canal, which is a canal structure built to entirely avoid a section of the river. The sluice was built to deepen a pre-existing divot on the south side of the river and navigate around an island that the river has since reduced to a pile of rocks. While the river is entirely located in Maryland, the island indicates that the sluice was in Virginia during its construction.

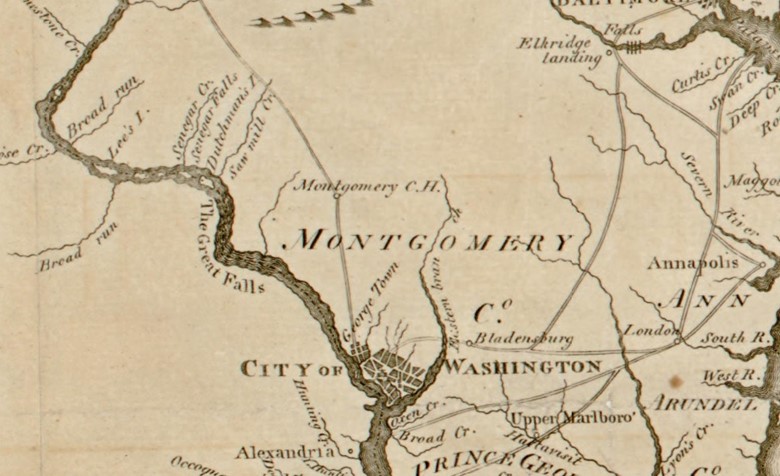

Early in the 18th-century, surveyors determined that the Potomac River was one of the best waterways for connecting the east coast with the Ohio River Valley, and potentially even the Mississippi River to the south and Great Lakes to the north (Bacon-Foster 1912:66; Guzy 2011:9). As waterways were the highways of the 18th-century, this connection would have been crucial in the advancement of trade and travel between the colonies and the territories. However, the river had some serious obstacles, including Great Falls, that the company would have to address before the river could be fully navigable.

The Patowmack River Company formed after the American Revolution and immediately began making improvements to the river's navigation. As president of the newly formed Patowmack River Company, recently retired General George Washington was able to use his reputation and influence to encourage the bordering states of Virginia and Maryland to collaborate on the funding of the project. The newly formed state governments were desperate to pay off the debts incurred during the war, and the project served as a catalyst of economic growth in the region. The company was chartered by the Maryland and Virginia legislatures in 1784 and 1785, respectively (Guzy 2011:10).

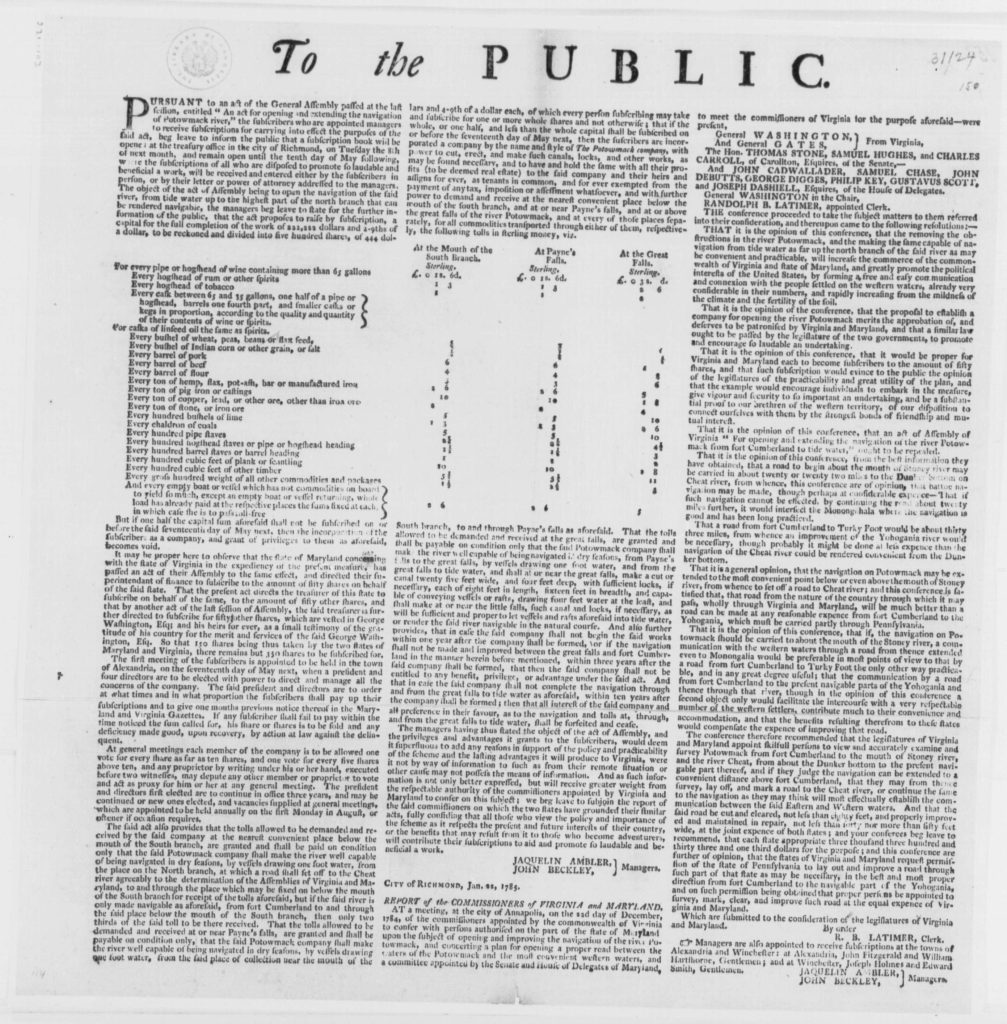

Funding came from subscriptions that members of the public could buy, investing in the company. Most of these subscribers had farms and industries located along the river and would benefit from the river’s navigability for trade. Their subscriptions made them shareholders in the enterprise and encouraged maintenance and development of the navigation. These advertisements, like the one shown below, explained the tolling system used on the river to assist in paying for the upkeep of the river (Bacon-Foster 1912:47).

The fifty-seven miles between the mouth of the Shenandoah River and the tidally influenced waters of Washington, DC were some of the most arduous to navigate. Three of the company’s four major navigational works were within this section: canals and locks at Great and Little Falls and a sluice at Seneca Falls (Guzy 2011:69). The Great Falls marked a significant shift in the navigability of the river because river waters upstream of the falls are not impacted by the tidal waters downstream.

More common were the smaller navigational features made throughout the section, including the Riverbend Sluice investigated in this survey. One such in-river sluice is in the five mile stretch between Seneca sluice and Great Falls (see Figure 4). According to the company’s annual report in 1792, this section “has been made Safe and easy by making it Straight in many places, removing Rocks, throwing up Dams to Collect & Deepen the Water where it was necessary” (Guzy 2011:74). A variety of labor, including hired hands and indentured servants were used, however it is important to note a significant amount of the work on the river’s features were conducted by enslaved laborers.

By 1795, the tidal Potomac was made more accessible with the construction of a canal and three wooden locks at Little Falls; the only portage required was at Great Falls. Stone locks around the Great Falls were finished in 1802, and boats with a variety of cargo including flour, pig iron, tobacco, and rum, among many others, traversed the seventy-seven-foot falls. However, the cost of maintaining the infrastructure frequently outweighed tolls and share sales (Guzy 2011:35).

In addition, the construction of the Erie Canal, finished in 1825, encouraged a nationwide shift away from the costly maintenance of river navigation, initiating the construction of a Potomac Canal, entirely separate from the river. Surveys in the 1820s cemented this shift away from river navigation and contributed to the end of the Patowmack River Company (Guzy 2011:14).

There were some attempts to save the Patowmack River Company by giving them the rights to build the canal. However, the company’s shareholders, who had hardly seen a dividend in the life of the company, were wary of taking on such a costly project, estimated to be fifty times greater than the cost of maintaining the river’s navigability (Bacon Foster 1912:104; Guzy 2011:15).

A separate company, the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal Company, formed to build a canal on the north bank. In August 1828, the Patowmack Company dissolved, and the new C&O Canal Company received the Patowmack Company’s former assets (Guzy 2011:18). Remnants of the navigational works of the Patowmack River Company remain as a testament to early enterprise of the upper Potomac River valley.

References

Bacon-Foster, Cora.

1912 Early Chapters in the Development of the Potomac Route to the West. Columbia Historical Society. Washington, D.C.

https://ia800708.us.archive.org/19/items/cu31924028867716/cu31924028867716.pdf George Washington’s Mouth Vernon

2022 The Potomac Company. George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/the-potomac-company/

Guzy, Dan.

2011 Navigation on the Upper Potomac and its Tributaries. WHILBR—Western Maryland Regional Library. Hagerstown, MD.

Library of Congress.

1785 George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Virginia Legislature, Public Announcement of Potomac River Navigation Company Subscription. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw435150/.