Virginia Landmarks Register Spotlight: Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives

Four landmarks across the Commonwealth illustrate the enduring architectural and cultural significance of Virginia’s once-ubiquitous roadside establishments.

By Austin Walker | DHR National Register Program Manager

With the increasing popularity of automobile ownership and travel from the mid-1930s onwards, a new architectural niche emerged along Virginia’s rapidly expanding roadways: restaurants and other establishments that could provide warm comfort and home cooking to passing motorists. With the goal of quickly capturing attention from potential customers in motion, these roadside eateries adopted a variety of eye-catching aesthetics, from the streamlined and shimmering stainless-steel of European industrial design to more novel and eclectic combinations of traditional and Modernist influences. Though corporate fast food would come to dominate the roadside landscape by the end of the 20th century, a small collection of buildings currently on the Virginia Landmarks Register highlights both the variety and evolution of diners and other destinations that once defined the Commonwealth’s major thoroughfares.

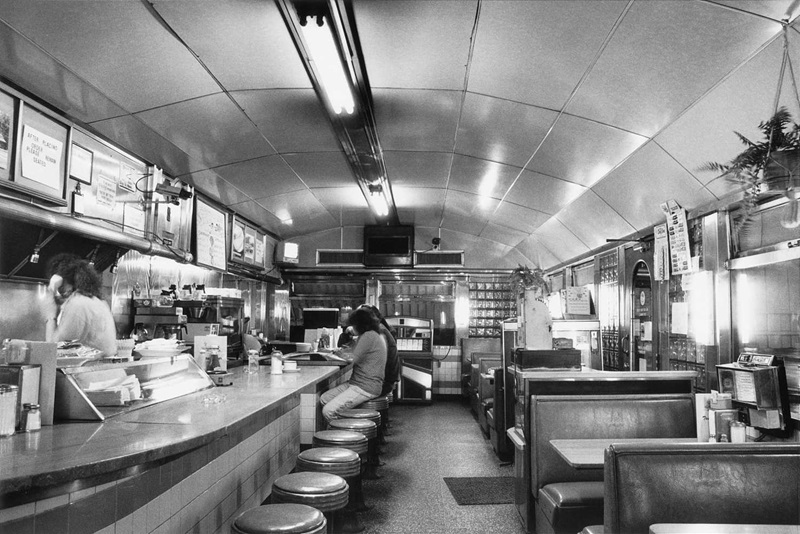

Now nestled amidst intense commercial development within the city of Fairfax, the 29 Diner is a rare surviving fragment of the roadside architecture that once lined Route 29, a major thoroughfare between the Washington D.C. area and the northern Virginia countryside. Like many streamlined Moderne diners of the era, the original building was prefabricated—it was designed and constructed by the Mountain View Diner Company of Signac in New Jersey and trucked to its present site, arriving on July 20, 1947. All exterior and interior features, including the back bar kitchen equipment, were installed before shipment. Owing to the high standard of craftsmanship championed by Mountain View, the 29 Diner remains highly intact and exhibits numerous high-style elements, including its aluminum monitor roof (reminiscent of trolley and rail cars), rounded glass brick corners, stainless steel prows, blue porcelain enamel panels, and interior ceramic tile. In near-continuous operation—and often open 24 hours a day—until a kitchen fire in November 2021, the 29 Diner still stands as a premier example of a uniquely American form of architecture.

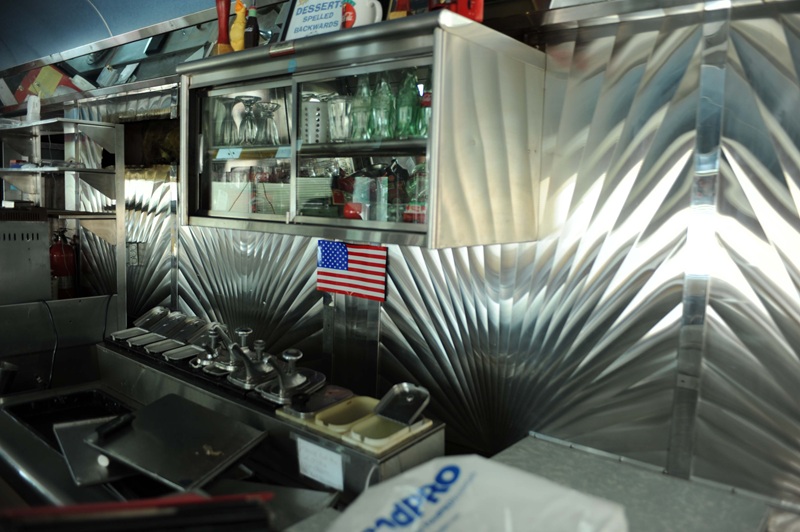

A similar history can be traced through Winchester’s Triangle Diner, aptly named for its strategic location at the intersection of U.S. Routes 11, 50, and 522. The prefabricated dining car was built by the pioneering Jerry O’Mahony Diner Company of Elizabeth, New Jersey, and delivered to Winchester via train in 1948. In addition to its remarkable stainless-steel exterior, the building featured polished terrazzo floors, blue Naugahyde booths and stools, a blue-and-yellow Formica counter, and a stainless-steel back bar with sunray-patterned wall panels. Along with the 1955 Frost Diner in Warrenton, the Triangle Diner is one of only two known stainless-steel O’Mahony diners in Virginia. In addition to its architectural significance, the diner also holds an important link to local history—Winchester native and country music legend Patsy Cline is said to have worked there as a teenager to help support her mother and younger siblings.

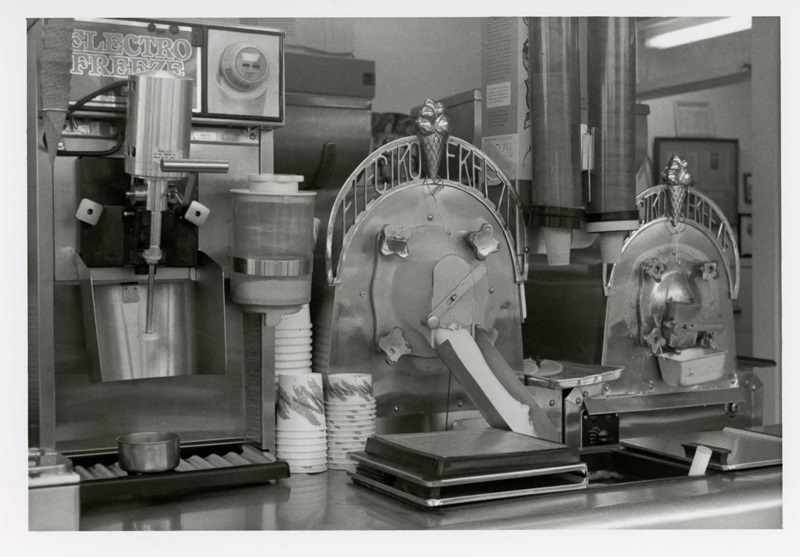

Elsewhere in Virginia, mid-century modern aesthetics were adapted for bespoke roadside landmarks. Located prominently along Princess Anne Street (US 17) just north of downtown Fredericksburg, Carl’s first opened as a frozen custard stand in 1947 in an abandoned gas station and restaurant. The current Moderne-style building was constructed in 1953 by local contractor Ashton Skinner and features many hallmarks of mid-century roadside design, including steel framing and plate glass windows, a “marquee” roof sheltering the walk-up service area, and a striking neon sign designed by original owner Carl Sponseller. When the building was listed in the early 2000s, the interior still housed three Electro-Freeze ice cream machines dating to the 1940s. Carl’s continues to operate as a retail ice cream stand and remains not only a local landmark but also an important meeting place for the community.

In contrast to the Moderne and Modernist influences seen above, The Coffee Pot in Roanoke embodies two other distinctive roadside architectural styles—the Rustic and the mimetic. Originally constructed as a tea room and filling station along Route 221 by Clifton and Irene Kefauver in 1936, the Coffee Pot quickly evolved into a roadhouse where locals came to dance, drink, and socialize. The building is clearly designed to attract passing motorists, combining a fantasy-sized log cabin-style structure housing a dining area, dance hall, and bar with a bright red, 15-foot-high “coffee pot” clad in stucco and sheet metal. An exemplar of the mimetic or “duck” architecture that became increasingly popular during the 1920s and ‘30s, The Coffee Pot is a singular work of 20th century roadside architecture on the Virginia Landmarks Register—though, incidentally, not Virginia’s only “Coffee Pot”—and remains in operation as a well-known local entertainment destination.

Diners, drive-ins, and dives comprise only a fraction of Virginia’s mid-20th-century roadside architectural legacy, but their inherent social and cultural importance as gathering places, along with their eye-catching architecture, afford them a special place among Virginia’s historic landmarks. As such buildings become increasingly rare, those that survive—and even remain in operation—will no doubt continue to grow in significance.